MONDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 1847

Before the Attack

...After

the noonday meal on Monday, November 29, 1847, the men returned to their

respective tasks and the children went back to school. John Sager went

to the kitchen where he continued winding a skein of brown twine preparatory

to making a broom. Mary Ann Bridger was in the kitchen washing the noonday

dishes. Mrs. Osborn, who had been confined to her bed in the Indian room

for about three weeks, ventured to get up and get dressed. She was very

weak. She walked into the living room where she saw Dr. Whitman reading

and Mrs. Whitman bathing the two older Sager girls. A tub of water had

been placed on the floor in the room. Catherine had just been bathed and

was dressing; Elizabeth was still in the tub.

The tragic events

began when Narcissa went into the kitchen to get milk for some of the

sick children. She found the room full of boisterous Indians whose manner

alarmed her. One demanded the milk she was carrying. According to Catherine's

account: "She told him to wait until she could give her baby some. He

followed her to the door of the sitting room and tried to force his way

in, but she shut the door in his face and bolted it."

48

Marcus Whitman, Mortally

Wounded

As soon as Narcissa

was able to fasten the door, an Indian began pounding on it, calling for

the doctor and asking for medicine. Dr. Whitman, laying aside his book,

arose and answered the knock. As he unbolted the door, an Indian tried

to force his way in, but the doctor succeeded in keeping him out. The

Indian demanded medicine, which the doctor promised to get. Whitman closed

and locked the door; went to the medicine cabinet located in a closet

under the stairway, and got what was needed. As he returned to the kitchen

door, he advised Narcissa to lock it after him. It was then about two

o'clock in the afternoon.

Catherine tells what

then happened: "We could hear loud and angry voices in the kitchen and occasionally

Father's soft, mild voice in reply

…Suddenly there was a

sharp explosion -- a rifle shot -- in the kitchen, and we all jumped in

fright for the outside door." Narcissa's first impulse was to rush into

the kitchen to see what had happened, but she quickly controlled herself.

Her immediate concern was for the safety of those with her. She called back

those who were starting to go out-of-doors. She began dressing Elizabeth

who had leaped out of the tub. Turning to Mrs. Osborn, she told her to go

to her room and lock the outside door. Mrs. Osborn called her husband to

do this. He, not having a hammer handy, used a flatiron to drive a nail

over the latch.

Suddenly Mary Ann Bridger,

who was the only eyewitness to the attack on Dr. Whitman and John Sager,

burst into the living room through the west door. She had fled out of the

north door of the kitchen and around the north end of the building. At first

the child was so incoherent with fright that she could not speak. Narcissa

grabbed her and asked: "Did they kill the doctor?" Mary Ann finally stammered:

"Yes." Catherine recalled that Narcissa cried over and over: "My husband

is killed and I am left a widow!"

Soon Mary Ann was able

to tell what she had seen. She told that the Indians had crowded into the

kitchen, including Tiloukaikt and Tomahas, the latter being the one who

had demanded the medicine. When Whitman entered the room, he sat down at

a table facing Tiloukaikt. According to Spalding's account, who drew upon

the child's recollections: "While . . . [Tiloukaikt] engrossed the doctor's

attention, Tomahas stepped behind him, drew a pipe tomahawk49

from under his blanket, and struck the doctor's head. He fell partly forward.

A second blow on the back of the head brought him to the

floor." 50Catherine added

more details: "Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor's face so badly that his features

could not be recognized." An Indian shot the doctor in the neck, causing

profuse bleeding. This was the shot which those in the living room heard.

Although fatally wounded, Whitman remained alive for several hours, most

of the time unconscious.

As soon as John Sager

became aware of the attack on Dr. Whitman, he grabbed a pistol, which might

have been the gun he had used to kill the beef then being butchered, and

shot twice, wounding two of the Indians.51

John, was then shot by Tamsucky. 52

He received a severe wound in the neck which began to bleed profusely. He

had enough consciousness to stuff a part of the scarf he was wearing into

the wound to staunch the flow of blood. A sudden commotion outside caused

the Indians in the kitchen to rush pell-mell through the south kitchen door

to join in the killings taking place there. They left Marcus Whitman and

John Sager, both mortally wounded, lying on the floor.

The

Attack Out-of-Doors

Following the noon

meal on that fateful Monday, Judge Saunders had reassembled his pupils

in the schoolroom. The number was smaller than usual because so many of

the children were ill. The sudden shooting and the tumult outside naturally

brought all activities in the schoolroom to a sudden halt. The half-breed

boy, John D. Manson, who was thirteen years old at the time, in his recollections

of that tragic day wrote: "While out at school recess, we saw eighteen

or twenty Indians standing around the Mission Premises and they were watching

three men dressing a beef. They were clothed with blankets strapped around

their waists with belts. When Mr. Saunders, our teacher, rang the bell,

we went back to the school room. Very soon a number of shots were fired

and Mr. Saunders looked out and saw Mr. Kimball running to the Doctor's

house. His arm was hanging limp and bleeding. Mr. Saunders crossed the

room and said, 'I must go to my family.' . . . We boys went to the window

and saw that the Indians had dropped their blankets and were running about

with their weapons in their hands, shooting and shouting."53

Pandemonium reigned.

It is impossible to give an accurate chronological account of what took

place, for the eyewitness accounts differ. Perhaps the first to be killed

was Marsh who was operating the gristmill. His death was probably instantaneous

as none of the survivors listed him as being among the wounded.

Another killed during

the first few minutes of the attack was Hoffman, who was the only one of

the victims who was able to offer any effective resistance. Catherine wrote:

"Mr. Hoffman was butchering beef and fought manfully with an ax and was

seen keeping several Indians at bay. He felled several with powerful blows

from his ax, and split one of his assailant's feet before he was finally

overpowered. They disemboweled him." 54No

doubt this mutilation was the result of the angry resentment of those whom

he had wounded. There is no evidence that the Indians scalped any of their

victims.

Catherine Sager, who

was standing with Narcissa looking through the upper part of the east door

of the living room, which was a window, saw the Indians attack Saunders.

Of this she wrote: "Mr. Saunders had commenced school at one o'clock. Hearing

the explosion [i.e., the rifle shots] in the kitchen, he ran down to see

what caused it. Mother saw him just as he got to the door. She motioned

to him to go back. He ran back, and had just got to the stairway [consisting

of two or three steps] leading up to the school, when an Indian seized him,

but being an active man, the Indian could not master him. I watched the

struggle from the window. Sometimes the savage would throw him, but he would

bound to his feet again, never losing his hold of the first one. I looked

till my heart sickened at the sight. Mr. Saunders wrestling for life with

those ruthless murderers, and they with their butcher knives trying to cut

his throat. He got loose from them and had got almost to his door . . .

before he was overpowered. His body was pierced with several balls when

he fell. They beat his head till it was mashed to pieces."

Elizabeth Sager testified

at the Oregon City trial, held in May 1850, that she saw Ish-ish-kais-kais

shoot Saunders. Osborn in his testimony given at the same trial said that

Tomahas was one of those who took part in the attack. Mrs. Hall, who was

watching the horrifying events from a window in the emigrant house, thought

that the Indians were attacking Dr. Whitman, and so testified at the trial.

She then claimed that Tiloukaikt was one of the assailants. Both Catherine

and Elizabeth Sager, however, claimed that Mrs. Hall was mistaken, as Dr.

Whitman was never able to leave the kitchen after being struck down. Matilda

Sager remembered that after the Indians had killed Saunders, they cut off

his head.55

Among those who witnessed

the attack of the Indians on the three men who were butchering the beef

and on the schoolteacher was twelve-year-old Nathan Kimball, Jr. After

more than fifty years, Nathan was able to recall with vividness the events

of those days. Regarding the mutilation of the bodies of the victims,

he wrote: "The bodies, or pieces of them, lay scattered all around, an

arm here and a leg there. Some of the men had their breasts torn open

and their hearts taken out. I saw two Indians each with a stick and a

human heart stuck upon it, which they showed to the women, and told them

that they belonged to their husbands, and that they were going to eat

them. I don't think they did but I don't know."56

Three men, Gilliland,

Kimball, and Rodgers, after being seriously wounded managed to find temporary

refuge in one of the mission buildings. Gilliland, according to Catherine's

account, "was sitting upon his table sewing, (when) an Indian stepped

in, and shot him with a pistol."57

Mrs. Saunders, who was in a room of the emigrant house next to that occupied

by Gilliland, ran to see what had happened after hearing the gunshot The

Indian later identified as Ish-ish-kais-kais, pointed his pistol at Mrs.

Saunders." 58She turned

and fled to her room. Gilliland soon followed. In terror, Mrs. Saunders

closed the door, shutting out Gilliland, as she thought he was an Indian.

Finally, hearing him call: "Let me in, let me in," she opened the door

and admitted him. Catherine wrote: "He ran and hid under the bed but soon

came out saying, 'It's no use to hide.' He lay down on the bed and died

quietly about midnight."

Nathan Kimball, Jr.,

saw an Indian shooting at his father who was trying to escape. The father

had been shot in the arm and the son remembered: "My father had on a white

shirt, and I could see that his arm was broken at the elbow, for it was

red with blood." 59 The

father ran around the south end of the mission house and entered the living

room through the west door. Elizabeth Sager remembered that when he burst

into the room, holding his bleeding arm, he cried out: "The Indians are

killing us - I don't know what the damned Indians want to kill me for

- I never did anything to them. Get me some water."

60 Since Kimball was a religious man and

never swore, the expression "damned Indians" seemed so incongruous to

the little girl that she began to giggle. She fully expected Mrs. Whitman

to rebuke him "for swearing in the presence of children," but to her surprise

nothing was said. Instead, her foster mother hastily got water and began

washing the wounded arm.

Rodgers was at the

river getting a pail of water when the shooting began. Hidden by the fringe

of willows which grew on the banks, he could have escaped detection and

fled to Fort Walla Walla for protection. Instead, he rushed back to the

mission house. Catherine tells us: "Mother, while ministering to the wounded,

went here and there looking out to see what was going on. She had missed

Mr. Rodgers from his room and was anxiously watching to see if she could

see anything of him. At last she saw him running desperately toward the

house, several savages, their knives and tomahawks glinting in the sun,

close at his heels. She dashed to the door to open it but not before he

had broken the window with his hand as he sprang against it. As soon as

the door closed upon him, the Indians raised a deafening yell and went

to find new victims. He was shot through the wrist and tomahawked behind

the ear."61

Terror

Indoors

Narcissa's immediate

concern, after hearing the commotion in the kitchen, was the fate of her

husband. After the Indians there had rushed out-of-doors and silence had

come to the kitchen, Narcissa ventured to enter. To her horror, she found

Marcus lying half-conscious on the floor with his head in a pool of blood.

just at that time, three of the women who were living in the emigrant

house - Mrs. Hays, Mrs. Hall, and Mrs. Saunders - burst in through the

north kitchen door. With their help, Narcissa half carried and half dragged

Marcus into the living room and placed him on a settee. Of the scene that

followed, Catherine wrote: "She fastened the door and placed a pillow

under his head, and kneeling over him tried to stop the blood that was

flowing from a wound in his neck."62

Narcissa took a towel and some wood ashes from the stove and with these

tried to stop the bleeding. She asked him if he knew her. He replied:

"Yes," "Are you badly hurt?" "Yes." "Can I do anything to stop this blood?"

"No." "Can you speak with me?" "N-no." "Is your mind at peace?" "Yes."

He spoke only in monosyllables. Again and again, Narcissa cried out: "That

Joe! That Joe! He has done it all. I am a widow!" When Rodgers burst into

the room so suddenly, he at once saw the doctor lying on the settee and

asked if he were dead. Whitman heard the question and answered with a

weak "No." This was the last word he spoke; he then lapsed into unconsciousness.

Several times during

those terrifying minutes following the first shootings, Joe Lewis came

to the door of the living room and tried to enter. Catherine wrote: "He

had a gun in his hand and when Mother would ask, `What do you want, Joe?,'

he would instantly leave." Soon after Rodgers had entered the room, Narcissa

went again to the east door to look out through its window. It was then

that Ish-ish-kais-kais (Frank Escaloom), who was standing on the steps

leading into the schoolroom, raised his gun and shot her. Catherine wrote:

"Mother was standing looking out at the window when a ball came through

the broken pane, entering her right shoulder.63

She clapped her hand to the wound saying, `Oh! Oh!' and fell backwards.

She now forgot everything but the poor, helpless children depending on

her, and she poured out her soul in prayer for them, `Lord save these

little ones!' was her repeated cry." Catherine also recalled how Narcissa

prayed for her parents, saying: "This will kill my poor mother."64

Catherine's account

of what then happened follows: "The women began now to go upstairs; and

Mr. Rogers, too much excited to speak, pushed us upstairs. I said, 'Who

will take care of the sick children?' Let me take them up, too; don't

leave them here alone." Catherine was thinking of her two sisters, Louise

and Henrietta, and Helen Mar Meek, who were probably in beds in the Whitman

bedroom. From this time onward, Catherine assumed a responsibility far

beyond her years and became a real heroine of those tragic hours. The

sick children were carried to the attic room. Altogether thirteen frightened

people sought the doubtful safety of the upstairs room. These included

two wounded men, Kimball and Rodgers; five women, including Lorinda Bewley

who was in her sick bed; and the four Sager and the two half- breed girls.

In the meantime, Osborn,

remembering that the floor boards of the Indian room in which he and his

family were living, had not been nailed down, lifted several and hastily

got his wife, their three children, and himself under the floor. A three-foot

space gave them plenty of room to hide. "We lay there listening to the

firing," Osborn wrote in a letter dated April 7, 1848, " - the screams

of women and children the groans of the dying - not knowing when our turn

would come. We were, however, not discovered." 65

Years later, Nancy

Osborn, who was only nine years old at the time, had the following to

tell: "In a few minutes our room was full of Indians, talking and laughing

as if it were a holiday. The only noise we made was my brother, Alexander,

two years old. When the Indians came into the room and were directly over

our heads, he said: 'Mother, the Indians are taking all of our things!

Hastily she clapped her hands over his mouth and whispered he must be

still."66

Experiences of the School

Children

As soon as the school

children realized what was happening out-of-doors, they quickly shut and

locked the door. Francis (also called Frank) Sager suggested that they

climb up into a loft which had been built over part of the room for use

as a bedroom. Since there was no stairway to the room, nor was a ladder

then available, the children moved a table under the door of the loft

and piled some books on it. one of the older boys then climbed up and

helped the girls to enter. Among them was Matilda Sager, who, many years

later, wrote: "Frank told us all to ask God to save us and I can see him

now, as he kneeled and prayed for God to spare us."67

Just how long the

children remained hidden in the loft is not known, but sometime early

in the afternoon Joe Stanfield came calling for the two Manson boys and

David Malin. These came down from the loft and were then taken by Stanfield

to Finley's lodge which was located to the north of the main mission house.

Stanfield assured the boys that since they were part Indian, they would

not be harmed. The next day Finley took the three boys to Fort Walla Walla

where they were given into the custody of William McBean.

Soon after Stanfield

had taken the three half-breed boys to Finley's lodge, Joe Lewis entered

the schoolroom looking for Francis Sager in particular. For some reason

Joe had a special grudge against Francis and was bent on revenge. After

discovering that Francis and the other children were in the loft, Joe

demanded that all come down at once. They were then taken out into the

yard and lined up to be shot. After the departure of the Manson boys,

only Eliza Spalding could understand what was being said by the Indians.

She remembered that some of the Indians were opposed to killing the children.

Convinced that they would be killed, frightened Eliza covered her face

with her apron so that she would not see them shoot her."68

Catherine wrote: "There

they stood in a long row, their murderers leaning on their guns, waiting

for the word from the chief (possibly Tiloukaikt) to send them into eternity.

Pity, however, moved the heart of the chief for, after observing their

terror, he said: 'Let us not kill them."'

The children were

then taken into the Indian room. As they passed through the kitchen Francis

saw his brother lying mortally wounded on the floor. He leaned over and

by some sudden impulse pulled at the scarf which John had stuffed into

the wound in his throat. This was the wrong thing to do, as it opened

the wound and the blood began to pour out. John tried to speak but could

not. He died soon afterwards.

Francis sobbed and

said: "I will follow him." Some of the Indians taunted Joe Lewis and said

that "if he was on their side, he must kill Francis Sager to prove it."

69 After being thus taunted, Joe grabbed

Francis by the nose, jerked him forward, and called him "a bad boy." The

Osborns under the floor heard Francis pleading for his life: "O Joe, don't

shoot me!'' Then came the crack of a gun, "as Lewis proved his loyalty

to the red men." Francis fell at the entrance of the north door leading

out of the Indian room. At the trial of the five accused murderers held

in Oregon City, Clokamus admitted "that he assisted in dispatching young

Sager."70

Mrs. Saunder's Brave Intercession

In the meantime, Mrs.

Saunders, not knowing what had happened to her husband or to the Whitmans,

and fearing for the safety of all the white women and children, decided

to make a desperate appeal for mercy to Chief Tiloukaikt through Nicholas

Finley. She bravely ventured to leave the comparative safety of her room

in the emigrant house in order to call on Finley in his lodge. John Manson

was at the lodge'. when Mrs. Saunders arrived and has given us the following

account of what happened. Since he was able to understand what the Indians

were saying, his recollections have special significance.

Soon Mrs. Saunders

came up to the lodge where Mrs. Finley [an Indian woman], her sister and

several other Indian women were standing. Besides the Cayuse Indian women,

there were some Walla Walla Indian men. The women seemed friendly to Mrs.

Saunders.

About four hundred

feet away from the lodge was a hill that had three Indians on it, looking

over the plains. [Possibly looking to see if anyone were approaching.]

One of the Indians rode down to kill Mrs. Saunders, but Mrs. Finley

expostulated with him and he rode off. Then Chief Tiloukaikt rode down,

shaking his hatchet over his head. He threatened Mrs. Saunders with

it, but again Mrs. Finley urged him to desist and he rode off. Then

Edward Tiloukaikt, the oldest son of the Chief, rode down very rapidly,

shaking his tomahawk over his head and that of Mrs. Saunders with fury.

She had sunk down on a pile of matting in front of the lodge. But the

Indian women shamed him and talked to him. Then he rode off.

Mrs. Saunders then

came to me [John Manson] and kneeled down. She begged me to interpret

for her to the Chiefs, as she did not understand the language of the

natives. She said: 'Tell the Chiefs that if the Doctor and men were

bad, I did not know it. My heart is good and I want to live. If they

will spare my life, I will make caps, coats, and pantaloons for them.

John interpreted for

her as she pled with Tiloukaikt for the life of her husband and for the

women and children. In all probability her husband by that time had been

killed, but of this she was unaware.

"What do they say,

John?"

"They are talking about it."

After some consultation,

Tiloukaikt and the other chiefs agreed that none of the women and children

would be killed. Mrs. Saunders then begged to let all who were in the

main mission house go to the emigrant house. Tiloukaikt gave his consent.

Mrs. Saunders then

turned to John, while still on her knees, and begged: "John won't you

go home with me?" John replied: "I do not dare to go, but I will ask."

Tuloukaikt then told Stanfield to take Mrs. Saunders back to her quarters

and to get her some meat. John's account continues: "Then Mrs. Saunders

rose from her knees and went with Joe Stanfield. The Chiefs and all the

natives then left the lodge. They went to Dr. Whitman's house. Very soon,

several shots were fired there. Mr. Finley came and told us that three

more had been killed. They were Mrs. Whitman, Mr. Rogers, and Francis

Sager."

The

Deaths of Narcissa Whitman and Andrew Rodgers

The rampaging Indians,

after searching the main floor of the Whitman home for Mrs. Whitman and

other members of her family, finally came to the door leading to the attic

rooms. This had been locked from the inside but the Indians soon smashed

it open. "We thought our time had come," wrote Catherine. While the Indians

were still breaking down the door, Kimball said that if they only had

a gun, they could keep them at bay. Someone remembered that there was

the barrel of a broken gun in the attic room. Rodgers got it and held

it over the railing of the stairwell. As soon as the Indians, who began

ascending the stairs, saw the gun barrel, they hastily retreated.

None of the eyewitness

accounts pinpoint the rapidly passing events by giving the time. In all

probability all of the events described above, following the firing of

the first shot, came within an hour period. Catherine remembered that,

following the retreat of the Indians from the stairway, all was quiet

before for about half an hour. "We began to think," she wrote, "that the

Indians had left, when we heard footsteps in the rooms below, and a voice

at the bottom of the stairs called Mr. Rodgers. Mr. R. would not answer

for a time. Mother finally prevailed, on him to speak, remarking, `God

maybe has raised us up a friend.'" The Indian was Tamsucky. It was he

who, according to the best available evidence, was the one who had tried

to force his way into Narcissa's bedroom shortly after Marcus had left

for the East in October 1842. In a friendly voice, he told Rodgers that

he had just arrived on the mission grounds, knew nothing of the terrible

events which had taken place, and was then offering his help. Narcissa,

eager to grasp at any offer of aid in her hour of desperation, was ready

to throw herself upon Tamsucky's promise of aid and deliverance. Catherine,

however, had recognized Tamsucky as one of the Indians who had killed

Judge Saunders and advised caution. After some consultation the adults

in the upstairs room decided that they should listen to what Tamsucky

had to say.

Catherine tells us

what then happened: "Mr. Rodgers told him to come upstairs. He replied

that he was afraid we had white men there who would kill him. Mr. Rodgers

assured him of his safety. He then asked for Mother, and was told that

she was badly hurt. Mr. Rodgers finally went to the doorway and talked

with him, and succeeded in having him come where we were. He shook hands

with us all and seemed very sorry Mother was hurt; condoled with her on

what had happened until he won her confidence." When Tamsucky saw the

wounded Kimball lying on the floor, he muttered: "Bad Indian. Indian shoot."

Tamsucky then passed

on the terrifying information that the Indians were planning to burn the

mission house and that Mrs. Whitman and those with her should leave immediately

for the lodge of an Indian who lived ten miles away.

71 Narcissa, realizing that she was in no

condition to travel and also that it would soon be dark, told him that

they could not go at that time. Tamsucky then told her to go to the emigrant

house and spend the night there. In reality Tamsucky was scheming to get

her and Rodgers out-of-doors where the Indians could complete their bloody

designs. Narcissa was completely deceived by his duplicity, but then,

what else could she do except to follow his advice? She grasped at his

specious promises of protection.

Eager to return to

their families in the emigrant house, the three women hastily left. Going

with them was Lorinda Bewley who had arisen from her sick bed. Rodgers

helped Narcissa go down the stairs. She was so weak from the loss of blood

that she had to lie down at once on a settee. With her was Elizabeth Sager,

then ten years old, who never forgot how Narcissa averted her face when

she saw her husband, still alive but unconscious. 72

The sight of the bloody, mutilated head was too horrible to endure. Kimball

decided not to risk leaving the attic room, perhaps suspecting that Tamsucky's

promise of safe conduct to the emigrant house did not apply to him. Since

no one had been willing or able to carry the sick little girls to the

emigrant house, Catherine decided to remain with them. Also in the attic

room was Mary Ann Bridger.

Shortly after Narcissa

went down stairs, the Indians ordered Rodgers to help Joe Lewis carry

her on the settee over to the emigrant house. Even though Rodgers had

been wounded in the wrist, he seems to have been able to lift his end

of the settee. They moved from the living room through the kitchen and

out the north door of the kitchen. Elizabeth, who was following, noted

that her brother John's body "was lying across the doorway." As soon as

the settee bearing Narcissa had cleared the doorway, some Indians standing

near started firing. Elizabeth remembered: "I was still on the sill when

a shot from a row of Indians standing there struck Mrs. Whitman on the

cheek. I saw the bullet as it hit her. Mr. Rodgers set the settee down

on the platform at the doorway saying `Oh, My God!' and fell." He, too

had been struck with bullets. As Elizabeth turned to flee to the upstairs

room to rejoin her sister Catherine, she passed through the living room

where she slipped in a pool of blood. Upstairs, she stammered out her

story of what had happened. "The terror of that moment cannot be expressed,"

she wrote. "There were no tears, no shrieks." The awfulness of what had

happened stunned all, even the younger girls, into silence.

73

After a volley of

bullets had been fired into the bodies of Narcissa and Rodgers, one of

the Indians upset the settee and rolled her body into the mud, possibly

into an irrigation ditch. With fiendish delight, one Indian lifted up

Narcissa's head by grabbing her hair, and lashed her face with his braided

leather quirt. 74 Circumstantial

evidence indicates that Narcissa died at the time of this attack or shortly

thereafter. Rodgers, although mortally wounded, lingered on for several

hours in a conscious condition.

"As soon as it became

dark," wrote Nancy Osborn, "the Indians left for their lodges . . . Everything

became still. It was the stillness of death." The school children, released

by their captors, had fled to the emigrant house where Mrs. Saunders received

Matilda. Those in the emigrant house were ignorant of the fate of Kimball

and of the four girls who had been left in the attic room, but no one

dared go and investigate.

Nancy remembered

that while she with the other members of her family were still in hiding

under the floor of the Indian room, the stillness which had come to the

mission house was broken only by the groans of the dying. Dr. Whitman

died about nine o'clock that evening; Rodgers died later. "All we could

hear were the dying groans of Mr. Rodgers, who lay within six feet of

me;' wrote Nancy. "We heard him say, 'Come Lord Jesus, come quickly.'

Afterwards he said faintly, 'Sweet Jesus.' Then fainter and fainter came

the moans until they ceased all together.

The carnage for the

day was over with nine people dead -one woman, six men, and two boys.

Thus ended the earthly

life of Narcissa Whitman who, at the time of her death, was approaching

her fortieth birthday. And likewise the life of Marcus Whitman who had

lived nearly three months beyond his forty-fifth birthday. They were the

first Protestants to suffer martyrdom on the Pacific Slope of the United

States."75

Some

Were Weeping

Waiilatpu was

a place of contradictions on that bloody Monday afternoon. The violence

precipitated a dichotomy of emotions among the Cayuses themselves. Mingled

with hideous war cries were pleas of mercy. While some were killing, others

were weeping. Again it should be emphasized that only a small minority

of the Cayuses took part in the massacre, and they were largely if not

exclusively from Tiloukaikt's band. Most of the members of the Cayuse

tribe were either unaware of what had been planned or had refused to join

in the conspiracy.

Among those who objected

to the violence, and who did much to ameliorate the lot of the captives

after the massacre, was one whom the survivors called Chief Beardy.76

Possibly "Beardy" was a nickname bestowed upon him at the time of the

massacre by the grateful survivors. No mention of a chief by this name

has been found in the writings of the Whitmans nor do we know his Indian

name. The Sager girls and Mrs. Saunders make frequent mention of him.

He was described as having been one of the most faithful attendants at

Whitman's religious services No doubt the nickname was given because of

his hirsute appearance, unusual among the Indians.

Catherine wrote that

when Mrs. Saunders went to Finley's lodge, "She saw an Indian at Dr. Whitman's

house, talking and gesticulating for some time. He rode toward her, and

she saw that he was weeping."77

It was Beardy who

was vainly trying to get the other Indians to stop their killings. Mrs.

Saunders called to him, and he rode to her and went with her to the lodge.

Catherine wrote: "Whether it was her intercession or the speech of the

chief [i.e., Beardy] that turned the tide, I know not what, but the chief

[Tiloukaikt] heading the murderers said, 'It is enough, no more blood

must be shed. The Doctor is dead. The men are all dead. These women and

children have not hurt us and they must not be hurt.'" Actually at that

time, not all the men had been killed. Four more were to die, but the

women and children were spared. Perhaps much of the credit for this act

of mercy should go to the influence of Beardy.

Catherine, in summarizing

the events of the next day, November 30, noted that some of the Indian

women "cried over us and gave us many things." Again and again in the

reminiscences of the survivors, we find references to the grief of many

of the Cayuses who were shocked by the violence committed by some of their

own tribe.

Drury's

account of events at Waiilatpu on November 30, 1847

Top of Page

48Pringle

ms., p. 32

Back

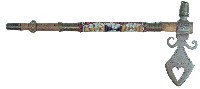

49Both Whitman College and Oregon Historical

Society claim to have the original tomahawk used to kill Dr. Whitman.

Web editor's note: It has since been determined that the Oregon Historical

Society in Portland, Oregon owns the tomahawk that killed Dr. Whitman.

Back

50When the bones of the victims were exhumed

in 1897, at the 50th anniversary of the massacre, the skull of Dr. Whitman

showed that he had received two blows from tomahawks. One cut out of the

back of the skull a piece about the size of a dollar; the other cracked

the skull on top. Oregon Native Son, I:63; Spalding, Senate

Document, p. 27...

Back

51Bancroft, Oregon, I:659. Bancroft,

however, does not give the source for this information.

Back

52Lockley, Oregon Trail Blazers, p.

355, quoting Elizabeth Sager.

Back

53See Chapter Twenty-One, fn. 29. The two

Manson boys, John and Stephen, were present during the first day of the

massacre and were then taken to Fort Walla Walla by Nicholas Finley. On

July 29, 1884, John, then fifty years old, wrote his recollections of

what he had seen and heard at the time of the massacre. These are important

since he and his brother knew the Indian language, thus he was able to

report what he had heard. My attention was called to the Manson statement

by Larry J. Waldon, Chief Interpreter of the Whitman Mission National

Historic Site, in a letter dated July 1, 1972.

Back

54Clarke, Pioneer Days, II:532. Probably

quoting Catherine Sager.

Back

55Delaney, A Survivor's Recollections,

p. 15. Helen Saunders Church in Whitman College Quarterly, II (1898):4:1

also tells of the killing of Judge Saunders.

Back

56Transactions of the Oregon Pioneer Association,

1903, p. 103.

Back

57Clarke, op. cit., II:534.

Back

58Saunders ms., p. 8. Since she did not know

the Indian by name, she identified him simply as being the one who later

shot Mrs. Whitman.

Back

59Transactions of the Oregon Pioneer Association,

1903, p. 189.

Back

60Lockley, Oregon Trail Blazers, p.

336

Back

61Pringle ms., p. 32

Back

62Lockley, op. cit., p. 336; Spalding,

Senate Document, p. 28

Back

63Oregon Spectator, May 30, 1850, reported

that "Isaiaasheluckes (Frank Escaloom)" confessed that he had shot Mrs.

Whitman, Elizabeth and Matilda Sager claim that she was wounded in the

left breast; Spalding and Catherine Sager, the right.

Back

64Clarke, op. cit., II:532.

Back

65Hulbert, Overland to the Pacific,

VIII:262.

Back

66See Appendix 5, for a listing of articles

by or about Nancy Osborn Jacobs.

Back

67Delaney, A Survivor's Recollections,

p. 17.

Back

68Pringle ms., p. 35. Also, Eliza Spalding

Warren in Ladies Home Journal, August 1913, p. 38.

Back

69Nancy Osborn Jacobs, Waitsburg, Wash., Times,

Feb. 2, 1934; also East Oregonian, Pendleton, May 19, 1919

Back

70Oregon Spectator, May 30, 1850

Back

71The identity of the Indian who was willing

to receive Narcissa is unknown. The fact that Narcissa was asked to travel

ten miles before dark is an indication that the incident described occurred

about 2:30 or 3:00 p.m. This is one of the few references to time in the

contemporary accounts of the massacre.

Back

72Saunders ms., p. 11. Mrs. Saunders claimed

that Narcissa "fainted at the sight of her husband lying dead before her."

Back

73From an interview with Elizabeth Sager Helm,

Whitman College Quarterly, I (1897):2:22

Back

74Delaney, A Survivor's Recollections,

p. 19.

Back

75The first Roman Catholic martyr, in what

is now the Pacific Slope of the United States, was Padre Francisco Garcés,

who was killed by Indians in 1781 at his mission across the Colorado River

from what is now Yuma, Arizona.

Back

76Even though Five Crows had been appointed

by Elijah White to be the Head Chief of the Cayuses, the head of each

family group or band was often referred to as a chief.

Back

77Pringle ms., p. 35. Italics are the author's.

Back

Top of

Page

|