Atrocities in the First World War

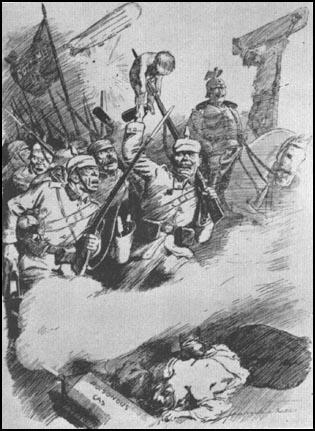

During the First World War most countries publicized stories of enemy soldiers committing atrocities. It was believed that it would help persuade young men to join the armed forces. As one British general pointed out after the war: "to make armies go on killing one another it is necessary to invent lies about the enemy". These atrocity stories were then fed to newspapers who were quite willing to publish them. British newspapers accused German soldiers of a series of crimes including: gouging out the eyes of civilians, cutting off the hands of teenage boys, raping and sexually mutilating women, giving children hand grenades to play with, bayoneting babies and the crucifixion of captured soldiers. Wythe Williams, who worked for the New York Times, investigated some of these stories and reported "that none of the rumours of wanton killings and torture could be verified."

In December 1914 Herbert Asquith appointed a committee of lawyers and historians under the chairmanship of Lord Bryce to investigate alleged German atrocities in Belgium. The report, published in 30 different languages, claimed that there had been numerous examples of German brutality towards non-combatants, especially towards old men, women and children. Five days after the Bryce Report was issued, the German authorities published its White Book. This included accounts of atrocities committed by Belgians on German soldiers.

Although soldiers from all countries were guilty of individual brutalities, research after the war suggested that these were isolated incidents rather than any systematic attempt to terrorize and punish the enemy. However, others have suggested it was fairly common to kill prisoners of war. Robert Graves pointed out in Goodbye to All That (1929): "For true atrocities, meaning personal rather than military violations of the code of war, few opportunities occurred - except in the interval between the surrender of prisoners and their arrival (or non-arrival) at headquarters. Advantage was only too often taken of this opportunity. Nearly every instructor in the mess could quote specific instances of prisoners having been murdered on the way back. The commonest motives were, it seems, revenge for the death of friends or relatives, jealousy of the prisoner's trip to a comfortable prison camp in England, military enthusiasm, fear of being suddenly overpowered by the prisoners, or, more simply, impatience with the escorting job."

Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier argued in his book, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930): "The British soldier is a kindly fellow and it is safe to say, despite the dope, seldom oversteps the mark of barbaric propriety in France, save occasionally to kill prisoners he cannot be bothered to escort back to his lines."