|

In the university city of Cambridge, England, a group of scholars discussed the increasing amount of research material being produced on Rennes-le-Château, the enduring mystery of a French priest who appears to have discovered a great treasure or secret while renovating his church in the early 1890’s. The focus of the discussion was the assessment of either the poor supportive evidence of the theories and conclusions offered at the time, or how subsequent publications simply propagated earlier weak theories or poor conclusive research.

The team concluded that the events of Rennes-le-Château warranted the public’s attention, and they themselves were fascinated by the existing oddities, although they believed that many readers’ efforts in making informed investigations were being hampered by having access to only the most easily available material - the mainstream ‘High Street’ publications.

The group resolved to attempt to offer such readers and researchers an alternative source of information. Using their access to academic resources, they could provide not only a database or publication that did not claim to offer the ‘Pulp Fiction’ solutions, but also direct and full background material on all the topics that the previous publications had failed to explain or research fully.

The project had no agenda or belief in solving any historic question or issue, but wished simply to provide information that was available to the breadth of disciplines represented by the members of the group. There was no general consensus to regard the events of Rennes-le-Château as either a true historic phenomenon or an intended (or unintended) hoax, although the scholars readily admit that they did have a fascination regarding the coincidences relating to the publicly known activities of priests of the region and the oddities in the design of the church’s refurbishment. Even so, the group remained open-minded that these were merely coincidences, which only fuelled later hoaxes and over-enthusiastic researchers.

The group also readily concedes that significant members of the group are/were members of certain known clubs and societies, and religious faiths, but at the beginning of the project these facts were not noted as any single point of significance. Neither were these individual memberships the source of any original interest in the subject matter.

From an academic background the project was not a difficult process to break down and research:

-

Cultural Historical Evidence – looking into the historical and theological sources of the material that is most commonly referred to in the existing investigations.

-

Historical Evidence – looking into physical evidence that can be sourced regarding the ‘Ground Zero’ of events; the lives of the priests and immediate supporting characters, and the modern characters that have ‘exposed’ the enigma.

-

Cross-Reference – confirming any genuine link that may exist between Cultural Historical Evidence and the ‘Ground Zero’ evidence.

With access to source Cultural Historical material and the academic credentials to access the Historical Evidence, the group made substantial steps in creating the central core of the database they were attempting to forge.

However, it was through the final process, the ‘Cross-Reference’, that an unexpected ‘discovery’ was made; a discovery that initially created an academic paradox, which the scholars could not answer. In essence, they had discovered that a piece of knowingly false information, which they felt had already been proven false without their research, was actually genuine, thus creating a paradox. A document that is believed to be a hoax does, in fact, contain solid clues to reveal a genuine ‘secret’ that has been protected for at least 400 years. Hence, the closing part of the academic paradox: how could the authors of the hoax be aware of the ‘secret’, which has been protected for 400 years, only to be discovered, ‘or exposed’, by the group?

From this point the group’s research focused on the confirmation of the discovery. Once confirmed, this academic anomaly changed the intent of the project. Although still intent on public awareness, they agreed they could not, even if only to protect their own academic standing, offer the information without fully understanding and explaining the paradox.

In explaining the paradox it became evident that the meaning and source of the information did indeed link to a society of which certain members of the group of scholars were already privately members, and therefore subject to personal oaths not to disclose any internal working of that society. This caused an internal issue within the group: how to reveal the confirming and supportive evidence of the meaning and understanding of the ‘discovery’ and its deeper consequences regarding the ‘myths’ of Rennes-le-Château.

The group then decided on a course of action, which would address both this ethical dilemma and an additional concern that had been expressed: how to ensure that material would be understood in full by those who read it, and that the academic evidence could be appreciated by more than those who benefited from having similar academic backgrounds such as theirs.

One scholar explained this concern in the following fashion:

‘Say that the secret was E=MC². This equation is known across the world. The general understanding of it is that it is a key formula that can explain almost every physical process, possibly even the Big Bang. So, to discover that this was known centuries before Einstein scratched it on chalkboard would be an impressive discovery. Although, if a person reading the research is already expecting the discovery to be a Golden Chalice, a Holy Grail, then they may not automatically accept that the answer is, in fact, a group of Letters and Numbers, even though it is true. For this you would need to show not only the evidence in full, but also what and why the simple sequence of Letters and Numbers could still hold the properties of the Holy Grail and yet not be a Golden Cup. This would take a lesson in Basic Quantum Physics and not everyone interested in Arthurian legends is willing to sit and read such things; hence, the evidence is ignored without being read and, as such, the discovery is ignored. To succeed we would need to teach Quantum in a fun fashion – if, of course, the answer was E=MC².’

So, in order to try and encourage the potential readers to understand the real, sometimes dull, but vital background information required, it was decided to release the information in the commercial format of Treasure Hunt Book Publishing.

In this way the discovery and supportive material were to be encoded in a series of books that encouraged readers to process the required background information in an attempt to solve each book in the series. This system of encryption worked, as the required educational process to reveal the ‘Quantum’ understanding was needed to appreciate the full significance of the first ‘Discovery’.

In order to gain the maximum audience possible, the decision was taken to advertise that the series would indeed reveal a ‘Long-Lost Secret’, and to offer a financial reward. The latter was not merely to gain market exposure, but also to ensure that the project would not be seen as a ‘Money-Making Exercise’. (The scale of the prize fund was £1 million Sterling and it would be highly unlikely that this amount would be raised by sales, thus confirming that the project was not for financial gain.) In addition, if a profit was indeed made, then one third of it would go to charity and the remainder would be used to repay those who were financially supporting the project, thus allowing the commercial aspect to become self-funded.

This series was created in the form of Maranatha – Et in Arcadia Ego/Timemonk. The complete collection consisted of six books, of which two were ultimately published - the original puzzle book and its companion. (The original puzzle book was re-branded in 2010, but contained the same material as the first publication.)

These first two books focused on the material that is being revealed here. The following information does not reveal all of the data encoded in the books already released, but does reveal the core material. Nor does this document reveal all the material sourced by the group, as this was divided throughout the complete series.

Unfortunately, the commercial efforts of this project failed. Some people have claimed that ‘powerful’ individuals have made clandestine efforts to suppress the work. True or not, the group does not believe this, although the group can confirm that the project has not been welcomed by all, and personal external agendas have also affected its success. Finally, though, the actual failure of the project was down to the world economic situation.

Even so, the personal pressures inflicted on the original group have been so immense and the scholars will not be continuing with any form of the project (excluding this release) or revealing the remaining material in their possession. This is now held for the group’s use only and has been held secure. This decision is purely due to the hostile reactions that have been inflicted and due to the membership of core individuals to certain societies and the oaths they have taken within them (all of which existed prior to the released publications).

For the material encoded in the first publication it is ideal to focus on the two parchments that were claimed to be those of the Priory of Sion. These documents were publicly revealed to have ‘encoded’ messages themselves. The Cambridge Group intended to review the authenticity of the documents and to review their origins and content.

The entire aspect of the Priory of Sion’s presence in the events and exposure of the Rennes-le-Château story is commonly accepted to be a hoax. With various aspects being publicly denied and confirmed, the Cambridge Group followed the opinion that the Priory was indeed a hoax.

Although...

In one of the documents this encoded phrase existed, which the group reviewed:

BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LE CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LE CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J'ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES

which is commonly translated as:

Shepherdess No Temptation That Poussin Teniers Hold The Key Peace 681 By The Cross and This Horse of God I Complete This Guardian Demon at Midday Blue Apples

The review of this encoded message created an academic paradox - and a discovery was made.

The first Maranatha – Et In Arcadia Ego publication focused on the first part of this encoded statement, up to and including the numbers 681. It was agreed that this segment was an ideal element to provide both a basis for readers to learn the fundamental material required for the full information of the series and, with the successful decoding of this first book, provide the public with evidence of the value of the material discovered and maintained by the Cambridge Group behind the series.

The opening part of the encoded message is commonly believed to refer to specific works of art by each of the stated artists, Poussin and Teniers. The actual works have been confirmed. The first is that of Nicolas Poussin’s The Shepherds of Arcadia (the second version). Although it shall be proven that the encoded message does, indeed, refer to Poussin’s second version of this particular scene, reference will be made to the original.

In investigating Poussin’s work, and especially regarding the letter to Nicolas Fouquet, attention was drawn to this painting. The group focused their research to see if any ‘discovery’ could be made within the painting itself. It was discovered that in numerous drawings by Poussin the paper or parchments he used contained ‘pin-pricks’, indicating that he used a set of compasses, or dividers, in the layout of his work. (It should be noted, however, that precise geographic layout and proportioning were common elements in classical art.) In addition, close inspection of the second version of The Shepherds of Arcadia revealed other anomalies, suggesting that this work of art was not completed in the standard fashion.

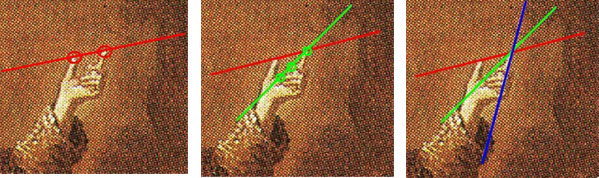

The investigation further concluded that the staffs of the shepherds appeared to have been painted before the depicted main tomb had been; especially the staff of the Red-Robed Shepherd on the right.

This is considered an extreme anomaly. In art it is standard, and ideally practical, to paint in layers, beginning with the background, then the mid-ground (the tomb) and lastly the foreground (the main characters), then returning to each to ‘touch up’ the finish.

The investigation showed that just behind the head of the Red-Robed Shepherd, where the staff should reappear and cross the tomb, the tomb is actually superimposed UPON the staff. It therefore appears (on close scrutiny) that the tip of the staff is emerging from BEHIND the tomb. This indicates that the tomb was painted after the staff was depicted.

In addition, a significant groove in the canvas was discovered running along the edge of the same staff. The way in which the paint covers this groove proves that it was made before the paint was applied, again indicating the significance Poussin placed on the location of this staff.

It is also worth stepping back to openly review, together, the two versions of The Shepherds of Arcadia completed by Poussin. Instantly, it is clear that they are completely different in appearance to each other. The original version is depicted in what could be termed a ‘soft’ and ‘fluid’ artistic style, while the second is ‘stark’ and ‘explicit’ in the way in which the characters and scene are portrayed.

It can also be noted that in the original version the classical hooked staff, in the centre of the painting, holds an anomaly. Where this staff is hidden by the shepherd’s body, the angle where it reappears is wrong, implying that there is a ‘kink’ in the shaft of the staff. It is also worth pointing out that none of the staffs of the three shepherds in the second version shows the same classically hooked staff, the standard anticipated emblem of a shepherd.

The final curiosity of the staffs in the second version by Poussin is the inconsistency in their lengths. The staffs of both the outer shepherds seem to be of a suitable length (although not equal), but the staff of the kneeling shepherd seems significantly shorter. Perhaps this is artistic licence, a device that stops it covering the face of the Cream-Robed Shepherd. If not artistic licence, then there must be a reason for the staff to be significantly shorter, for if the Blue-Robed Shepherd were standing, it would be more of a walking cane than a shepherd’s staff.

The final, significant difference between the two versions is the depiction of the characters. In the original they are ‘fluid’, almost ‘drifting’ into the scene. In the second version their posture and colours are more exact, especially with regard to the Red-Robed Shepherd; his own body appears distorted and held at an almost impossible angle, with his head twisted round to return the look of the female character.

Then, of course, there is the mystery of the scene itself. Virtually all classical art is either portrait or real scenic depiction, or a known mythical or Biblical/theological portrayal, familiar to the audience. It is extremely rare to see a scene that is not from one of these settings.

The scene of The Shepherds of Arcadia is not clearly representational of any known mythical or Biblical/theological scene. It has been linked to the writings of Virgil, but the tale is not clear, nor is the painting’s use of the inscription on the tomb – ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’.

Hence, it is possible to conclude that if anything was physically encrypted in the painting (with regard to Nicolas Fouquet), then the following seem to be specific points:

-

The angles of the bodies, significantly those on the right;

-

The lengths and angles of all the straight staffs;

-

The fingers that are pointing to the phrase on the tomb.

If a discovery could be made that employed all these points equally, then it could be considered a discovery beyond REASONABLE doubt.

This has been accomplished.

As stated previously, the staffs’ positions appear to be important, as they were painted first or, at least, their locations were set prior to the main process. Thus, the staffs are highlighted.

The ‘fault’ that appears behind the neck of the Red-Robed Shepherd lies on a line that can be drawn following the ‘line of sight’ of the female character, across the eyes of the awkwardly twisted head of the Red-Robed Shepherd. This divides the staff lines of both the Cream- and Blue-Robed Shepherds on the left of the painting.

The next stage is to follow the next curiosity referred to with regard to this painting: that of the peculiar short staff of the Blue-Robed Shepherd. A line can be drawn from the lower intersection of the ‘sight line’ up through the tip of the short staff.

From the same main intersection, confirmed by the last two lines completed, a line can be drawn to connect to the tip of the staff of the Red-Robed Shepherd. This will produce a line of exactly 45° from the base of the painting. It will also be a line that is exactly 60° from that of the staff of the Cream-Robed Shepherd. In addition, this will also confirm that the line that reaches through the tip of the staff of the Blue-Robed Shepherd is exactly halfway between both these lines, producing angles of exactly 15°. This is only possible with the exact angles, heights and positions of all three staffs - the only staffs shown.

The artistic focal aspect of the painting is the attention the Red- and Blue-Robed Shepherds pay to the inscription on the tomb, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’. Both are the only characters pointing to the tomb. A line can be drawn that connects the tips of both fingers and extends across the painting.

By extending the ‘Staff’ line of the Cream-Robed Shepherd to where the ‘Pointing Finger’ line would intersect, that point could be connected to the tip of the Red-Robed Shepherd’s staff. This would produce a perfectly proportioned equilateral triangle tilted at 45°.

As observed above, the pin holes discovered in other works of art by Nicolas Poussin indicate that he used a set of compasses or dividers to lay out his work. The lines of the ‘Pointing Fingers’ and the tip of the staff of the Blue-Robed Shepherd both divide their projected corners exactly in half, thus where they cross would mark the centre of the triangle. Using this point as a centre, a circle can be drawn so that it touches the three corners of the portrayed triangle.

Where the ‘Pointing Finger’ line and the Blue-Robed Shepherd’s line (which is extended from the tip of his short staff from the base corner of the triangle) cross the circumference of that circle, a line can be drawn to connect them.

A line can also be drawn from the tip of the Red-Robed Shepherd’s staff through the centre of the triangle to locate the missing point of the final triangle being produced.

From that location a complete and perfect hexagram, tilted to 45° can be formed. The significance of this shape and its tilted design will be covered later.

Before moving on, it is worth verifying the validity of this discovery by pointing out again that this perfect geometry is only possible due to the specific oddities of the painting. All of the non-hooked shepherd staffs would need to be at their precise location, angle and height (Blue- and Red-Robed Shepherds’ staffs) to produce the perfect geometry. Note that the Blue-Robed Shepherd’s staff would have to be short to produce its properties to the design structure. The Red-Robed Shepherd’s head would have to be twisted to produce the angle of sight, which is also where a known anomaly exists regarding the staff being painted before the tomb. The line that produced the first 45° angle also touches the heel and toe of the back foot of the kneeling Blue-Robed Shepherd. Further, the tip of the raised thumb of the Red-Robed Shepherd is on the line of the second triangle, while the pointing finger on the same hand is used to produce the perfect dividing line of the entire design, as is the second remaining pointing finger of the Blue-Robed Shepherd.

The painting by Teniers referred to in the Priory of Sion document is that of St Anthony and St Paul in the Desert, which was at one time reported to have been at Shugbourgh Hall. Originally recorded as being described as Elijah and Elisha, both titles are correct. (The group is asking the present owners of this painting to contact them if this material is of interest, as additional material is believed to be present.)

As with the description of the previous work by Poussin, we have not expressed all that has been encoded in these two paintings. This document simply refers to the direct translation of the first part of the encoded message of the so-called Priory Parchments.

The initial process to reveal the hidden geometry in this work is to note that the character of St Paul has both his thumb and index finger raised. A line can be drawn that touches the tip of both these digits and can extend to touch the second raven that can be seen flying in the distance. Note also that the line runs parallel to the crossbeam of the crucifix.

Following this, a line can be drawn from the intersection of the two staffs of the two Saints depicted. This line follows exactly the direction of St Paul’s pointing index finger. Further, a line can be drawn through the raven that is clearly carrying the bread to the Saints, using the bird’s wing tip and beak and dividing the bread exactly in half. This line also intersects at the tip of the pointing finger of St Paul.

These lines produce perfect dividing angles of 60° and 15° to each other.

Taking the intersection of the two staffs, a line can be drawn along the staff of St Paul. This line is exactly 15° to that of the line from the same corner that raises through St Paul’s index finger.

In addition, a line can be drawn from the same intersection on the staffs, through the tip of St Anthony’s staff (note that this staff is slightly bowed) and through the base of the crucifix. This line also engages with the 90° ridge in the cliff and crosses the line of the thumb and index finger of St Paul. This will produce a line of exactly 45° to the base of the painting.

Various methods can be used to complete the final design. It is possible to simply use a set of compasses. Using the tip of St Anthony’s index finger as the centre, and a radius with the distance from there to the intersection of the staffs, an encapsulating circle can be drawn. Alternatively, a line can be drawn that joins the tip of St Paul’s index finger, the top of the bottle on the rock, the stick that stands out on the base of crucifix and the base of the crucifix itself. This line will intersect exactly at 15° to the line produced by the staff of St Paul.

Joining the intersection on the ‘Staff’ line of St Paul and the line extended from the staff of St Anthony, a perfectly formed equilateral triangle is found, again set at 45°.

Using the tip of St Paul’s finger as the centre, a circle can be drawn that encases the triangle.

Using the existing construction lines a complete tilted hexagram can be produced.

As before, several points confirm the validity of the geometry. The angle of the crucifix, the wing tip and beak of the raven, the distant raven, the two staffs and the base of the crucifix, to say the least, are all perfectly placed and used in the design.

However, the main confirmation is the way in which these points merge on the hand of St Paul.

His fingers are perfectly positioned. The first line is produced by the thumb and raised index finger. The second line is created by the index finger tip and the tips of the remaining curled fingers. Finally, the actual direction of the index finger produces the perfect dividing line from the two resting staffs. This entire process makes the tip of the index finger the exact centre of the entire geometry.

In order to understand the significance of the design found in these two paintings, it is required to understand the geometric curiosities that the tilted hexagram produces.

The history of the study of geometry is easy enough for anyone to research, so there is no need to address that issue here. Although certain shapes and geometric curiosities were taught and, in some cases, revered, we need not concentrate too hard on this at this stage, but rather remember that we were all taught the value of π (Pi) during our schooldays, a value that is constant between any size of circle and its radius. Although this could still be regarded as a ‘geometric curiosity’, just as Platonic solids are, it has no special ‘power’.

The forming of the tilted hexagram or equilateral triangle is the same. It is produced using the three primary shapes of geometry: the circle, equilateral triangle and square. The design of a tilted equilateral triangle is a geometric curiosity, in that ‘the properties of two of the three shapes listed can produce the perfect form of the third’.

For example: starting with a square, an internal square could be added and twisted at 45°.

Inside the inner square a circle could be drawn.

Taking any corner of the larger square and projecting two lines out so that they touch the circumference of the inner circle, this produces an angle of 60°. Then, using the side of the tilted square that was opposite to the former corner, the extension of that side intersects with the two previously projected lines to produce a perfect equilateral triangle; a triangle set at 45°.

It is geometrically possible that the process could be completed no matter which shape one started with. An added curiosity is the fact that the exact centre of each shape is at precisely the same point as each other’s. Due to this, those who believed that geometry was the building block of life and/or creation (sacred geometry) saw this as the perfect presentation of the Trinity, either in an ancient form or in the Christian form; each shape is independent, but is also the sum of the other two.

(Obviously, a hexagram is easy to produce by reversing the final stage to create an opposing equilateral triangle.)

In the encoded sentence of the Priory Parchments, Poussin and Teniers are meant to ‘hold the Key’. A hexagram is called a ‘key’ in many theological stories and myths. In Freemasonry, which holds a fundamental reverence for the art of geometry, the hexagram is repeatedly referred to in various rituals and in its ceremonial jewels. In rituals that refer to the rediscovery of the so-called ‘Lost Secrets of Freemasonry’ it is very much a key element.

In higher degrees of Freemasonry (those that are still linked to legends forged in the Fellowcraft and Master Mason Degrees - the original two degrees of Freemasonry, although greatly changed today) candidates are given even deeper knowledge of how, where, what and why the Lost Secrets (and Treasure) were hidden. These higher degrees actually use the circle, triangle and square as their symbols. Indeed, the circle, square, triangle and hexagram are focal aspects of all the Degrees that relate to the Lost Secrets of Freemasonry. (Those who are aware of the Royal Arch Degree, in which the Lost Secrets of Freemasonry are said to be revealed, are respectfully reminded that there are several Degrees after this which will be of interest relating to the above).

Obviously, membership of the Order would confirm the information that is here and that which has not been expressed. Although Freemasons are asked to go and study the secrets of science and nature, this is offered to point out that the information is available elsewhere for those who wish to learn it.

To confirm that this symbol is indeed the key referred to in the encrypted message, attention is drawn to the next few words: Peace 681. The entire encoded message is originally written in French, except for the word and numbers, PAX 681, which are Latin.

It is understandable to use Roman numerals to represent numerical figures, but PAX is a pure Latin word. (PAIX is French for ‘peace’.) Indeed, it could be correct if 681 referred to a year, as PAX would imply a ‘peaceful’ period, so could mean that 681 was a ‘peaceful year’.

Instead, it was discovered that, like the Roman numerals, these letters hold individual values, rather than representing a single word; they should be seen as three letters, three Greek Letters: P, A and X.

The P and X refer to the Christian symbol of the Labarum, which found its source in a legend of Emperor Constantine (which is also found in a specific Masonic Degree). The Emperor received divine direction to combine the Greek letters, Chi (X) and Rho (P) (the first two Greek letters in the Greek spelling of Christ) to create a powerful design, as shown in figure (a) below.

Geometrically, this can be used to create the outer and twisted squares shown in figure (b).

It is classically common to see this symbol with two other Greek letters, A and Ω, Alpha and Omega, referring to the Biblical phrase of Christ, ‘I am the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and end’. (Again, this can not only be interpreted as Jesus Christ representing the complete journey to a theological salvation, but also that two extremely different elements can exist as one element at the same time). The A is already represented in the letters ‘P A X’, but just as P and X can be used to create the early stages of the tilted geometry, so can A and Ω.

Finally, the figure 681 represents simply the number of sides needed to produce the design: two triangles (six sides), two squares (eight sides) and one circle (one side).

This is as much information as the group feel that they can reveal with regard to the personal obligations that have been given. Yet this should be enough to honour the efforts people have put in to the publications released. Further information can be gained from the books that remain, Maranatha – Et in Arcadia Ego and its Companion, but the group will not offer any further comment.

Academically, it is possible that the individuals who composed the encoded sentence in the Priory Parchments were simply aware of the curious history of Poussin’s work. With their knowledge of the known enigma surrounding him and Nicolas Fouquet (the Vatican engraved copy of The Shepherds of Arcadia, the mystery behind the phrase ‘Et In Arcadia Ego’, Victor Hugo and Shugborough Hall, to name a few), they could have simply linked that perceived ‘mystery’ to the events of Rennes-le-Château.

Although the encoded sentence clearly states ‘Shepherdess’, ‘No Temptation’, ‘Poussin’ and ‘Teniers’, having found this perfect geometry in two paintings by two different artists, whose lives do not appear to be linked, and yet who are quoted in the same sentence, it is BEYOND reasonable doubt that the authors of the encoded phrase were at least aware of this ’key’ and where it was hidden (or were given the information in part, or in full, by another source).

The remaining part of the sentence, and the encapsulating importance of the complete message, indicates the ‘lock’ for this referred to ‘key’; a key to the treasure of Rennes-le-Château.

Priory Publications (GB) Ltd has ceased trading. We genuinely regret that these unfortunate events have occurred and hope that this article will satisfy those who engaged in the process we promoted. We hope that you continue in your work and wish you well. The staffs of the Saints and Shepherds are present in the drawings in Maranatha – Et in Arcadia Ego. As to the solution that has already been released, if the drawings of that publication were overlaid, it would be possible to reproduce the geometry shown here, and conclude the core material encrypted in that publication. The information that was set to be released in the remaining books of the projected series will not be released, for the reasons already given.

Duncan Burden

Time Monk

For further confirmation, Poussin also used the ‘key’ in his second self-portrait. A line can be drawn that passes through the eye of the female character depicted in the painting on the left of Poussin. This line passes through her eye and then through the eye on the crown she wears, extending up to cut the frame of the painting above. Then, using the right-angled corner of the larger frame on Poussin’s right, it is possible to produce a line of 45° for the key. Note that his robe is similar to that of St Anthony in the work of Teniers and has a stretch of fabric across his shoulders. Using this one can discover why Poussin painted the ring on his finger so that it faced the ‘on-looker’ and not where it would actually sit on the top of his finger. |