The Paperback Explosion:

How Gay Paperbacks Changed America

by Ian Young

![]() n an era when gay books are widely published and available, it can

easily be forgotten that not so many years ago - well within the span of a

lifetime - gay subject matter was taboo in the publishing industry. The

breakthrough came during and after World War II, when gay writing suddenly

emerged from the shadows to enlighten and scandalize a naive public. The new

Homophile movement of the Fifties and Sixties was accompanied by an

unprecedented upsurge of gay literature, and particularly of gay novels, in

both Britain and America. In a time when gay magazines reached only a small

number of people and gay themes seldom made their way into radio or film, gay

novels provided just about the only public information on homosexuality apart

from sensationalist newspaper accounts of prosecutions and scandals.

n an era when gay books are widely published and available, it can

easily be forgotten that not so many years ago - well within the span of a

lifetime - gay subject matter was taboo in the publishing industry. The

breakthrough came during and after World War II, when gay writing suddenly

emerged from the shadows to enlighten and scandalize a naive public. The new

Homophile movement of the Fifties and Sixties was accompanied by an

unprecedented upsurge of gay literature, and particularly of gay novels, in

both Britain and America. In a time when gay magazines reached only a small

number of people and gay themes seldom made their way into radio or film, gay

novels provided just about the only public information on homosexuality apart

from sensationalist newspaper accounts of prosecutions and scandals.

Students of gay history have become aware of the problems gay writers in the West had to face in those days. Gore Vidal's postwar gay novel The City and the Pillar was denied advertising space; James Baldwin's agent refused his Giovanni's Room; gay books and magazines were put on trial for obscenity. Though these were relatively minor matters compared to the fate of writers, gay or otherwise, in the East Bloc, nevertheless in both Cold War camps, new voices strained to be heard.

But the vicissitudes of advertising policy, the timidity of literary agents and even the attitudes of the courts were unknown to all but a tiny segment of the American public. Most people in small (or even large) towns knew nothing of these matters, and seldom saw any of the notorious books in question; that is, not until they came out in paperback and showed up on a rack in the local drugstore, soda shop or dime store. For many isolated young gays, that eye-catching 7" x 4 1/4" cover of Whisper or Rough Trade provided the first window onto the gay world.

Significantly, the rise of gay movements in the U.S. and Britain occurred at the same time as the Anglo-American paperback explosion. The wide availability of cheap paperback books helped spread the word about a sexuality and way of life that, until the war years, had been largely hidden from public view. Postwar paperbacks played an important role in the social and political developments of the Cold War years, and strongly reflected and influenced the emerging gay consciousness. Cheap, easily available paperbacks were as important to changing attitudes in the pre-Stonewall era as gay magazines and poetry chapbooks were in the Gay Liberation years that followed.

In the totalitarian society of the East Bloc, tight legal censorship had to be countered by a lonely, fearful trek backward to make innovative use of the technology of the past, samizdat, where forbidden texts were retyped and circulated secretly in carbon copies. In the West, looser de facto censorship could be surmounted by innovative technology to deliver the goods in a new way - and consequently, to produce a new kind of goods. The difference was in the distribution. In the West, where the means of distribution remained in private hands, new entrepreneurial approaches had a chance to develop. In the East Bloc, with distribution centrally controlled by government, new ideas had to tunnel under at enormous personal and social cost. America and the West prospered. The East Bloc stultified.

In Cold War America, the union of the Queer and the Beat, with a little help from the Junkie, produced the Freak. The liberated, post-Stonewall Gay was a late-blooming variety of Freak - the only one, as it happened, hardy enough to last - at least until 1981 when a death sentence was pronounced on him in the form of AIDS.

The notorious gay books of those Cold War years of DP's (displaced persons), JD's (juvenile delinquents), McCarthyism, and Vietnam included, in 1948 Truman Capote's Southern gothic Other Voices, Other Rooms; in 1950 Quatrefoil; in 1951 The Homosexual in America and Finistère; in 1952 Hemlock and After; in 1953 The Heart in Exile; in 1956 Giovanni's Room; in 1959 Sam and The Feathers of Death; in 1961 The Leather Boys; in 1963 City of Night; in 1964 A Single Man; in 1966 the "Phil Andros" hustling stories of $tud! From Other Voices, Other Rooms to $tud in the life of one eighteen year old!

All these titles were initially published in hardcover, but relatively

few people had a chance to hear of the books, and many bookstores - and even

libraries - did not stock them. An early example of this new species of

American literature, Charles Jackson's The Fall of Valor , a sombre study

published in 1946, was one of many never to make it through the gauntlet of

censorious librarians. "Subject, and especially bluntness of presentation,"

warned the Library Journal, "limit library use." Three years later,

Kirkus Reviews sniffed that as Nial Kent's treatment of the gay theme in

The Divided Path was "overt" rather than "fastidious," it was therefore

a novel "for the sensation seeker" who presumably should not be encouraged to

ascend the steps of the library.

, a sombre study

published in 1946, was one of many never to make it through the gauntlet of

censorious librarians. "Subject, and especially bluntness of presentation,"

warned the Library Journal, "limit library use." Three years later,

Kirkus Reviews sniffed that as Nial Kent's treatment of the gay theme in

The Divided Path was "overt" rather than "fastidious," it was therefore

a novel "for the sensation seeker" who presumably should not be encouraged to

ascend the steps of the library.

Busy pharmacists, Woolworths proprietors, malt shop managers and owners of general stores, however, were for the most part not burdened by these high-minded considerations. If a rack of garish paperbacks showing guys with guns, busty babes and an occasional pair of half-naked men could boost profits (and with a monthly turnover of titles anyway) there were few objections. Paperbacks - both original titles and reprints from previous hardcover editions - were an innovation that allowed the new gay literature to proliferate and find its readers outside the traditional bookshops and lending libraries. Reprinted in paperback, all the key titles listed above, and many more, found a larger, younger, more diverse readership.

***

Relatively inexpensive paperbound books had circulated in Europe as early as the 17th Century. The invention of the steam rotary press and the proliferation of railroad lines in the 19th Century allowed books to be produced and distributed cheaply and in large numbers. "Penny dreadfuls" and "dime novels" became enormously popular. And more dignified literary productions like the simple, elegant Tauchnitz and Albatross lines were promoted to the new breed of continental and intercontinental traveler, the jet-setters of their day. The invention of the typewriter led to the clacking sound of many hacks and an even greater outpouring of fiction. The Library of Congress has nearly 40,000 different 19th-Century dime novels, from 280 different series and countless authors, many using several pen-names. Horatio Alger published his influential morality adventures in this format - paperbound on cheap stock that tends to discolor, turn brittle and crumble with time.

By the 1890's, dime novels were beginning to be superceded by the many so-called "pulp magazines" like The Black Mask, which provided the young H.L. Mencken with an editorial desk. The heyday of the pulps, and pulp authors like Cornell Woolrich, lasted into the 1940's when World War II brought mass market paperbacks into their own again. In 1929, the American publisher Charles Boni pioneered a modest paperback line using a subdued, tasteful format and striking cover illustrations by Rockwell Kent. Haldeman-Julius' Little Blue Books and the orange-jacketed titles of Britain's Left Book Club each filled a specific need. But the real 20th Century breakthrough into mass sales was made by the Englishman Allen Lane with his Penguin Books in 1935. The Depression had caused sales of Lane's publishing firm The Bodley Head to plummet, and the first ten titles of the now famous paperback line were introduced to turn things around.

The experiment was a great success. The original Penguins employed superior type, paper and ink and plain but distinctive covers. Savings came through large print runs and sales at newspaper kiosks and railway stations all over Britain. Penguin soon opened a U.S. office, and the foundation for the post-war paperback boom was laid. Soon publishers like Popular Library, Fawcett Gold Medal and Ace (who published William S. Burroughs' first book, Junkie, bound back-to-back with another title) were all competing in what had quickly developed into a hot new market. In Britain, Pan, Corgi and Foursquare became important postwar paperback houses.

The war itself, which changed so much for America - and for Britain - gave paperbacks an enormous boost. To satisfy the Allied troops' hunger for portable reading material, the official Armed Services Editions were devised, with titles ranging from Melville, Whitman and Housman to useful tracts like Danger in the Cards: How to Spot a Crooked Gambler.

ASE's were distributed free to the troops, with 1,322 titles produced, many in print runs of over 10,000 copies. From this experiment, many men who had never before read for pleasure developed a taste for literature of one sort or another. The ex-servicemen who helped form the first Homophile organizations (and the first leather clubs) were among those readers. Women too, nudged by war out of their traditional roles, were ready to read. And the greater freedom young people discovered after the war involved a wider range of available reading material.

All this helped fuel the paperback revolution of the Forties, Fifties and Sixties, the era when America's traditional sexual mores were straining to free themselves. The Kinsey Reports, released in the late Forties and early Fifties, shattered the silence that allowed so many misconceptions about homosexuality to persist. The old attitudes about the Love that Dare Not Speak its Name were finished. But homosexuals - publicly discussed now, yet not truly visible - were becoming targets of Cold War paranoia. Whispers of homosexuality surrounded the Hiss-Chambers espionage case in 1948. Three years later, the revelation that the defecting British diplomats Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were homosexual or bisexual, added fuel to the fire. The fear reached its height in 1953. In America, Senator Joe McCarthy included homosexuals in his political witch-hunts - aided by attorney Roy Cohn and secretly assisted by F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover (all three, as it happened, were themselves deep closet cases). At the same time, Britain saw an alarming rise in anti-gay frame-ups and prosecutions, culminating in the notorious Lord Montagu case.

Gay campaigner Allan Horsfall has described the atmosphere of the time: "One felt that the police were ubiquitous and omniscient with their spy-holes and the secret surveillance and their agents provocateurs and their trawls through people's private diaries and letters." Many gay men fled abroad (if they could afford it) or destroyed incriminating personal papers.

Parallel to these events was the steady, year-by-year appearance of a series of revelatory gay novels. In 1951, Pyramid Paperbacks issued a revised version of The Divided Path, and two years later The Heart in Exile appeared at the height of the scandals. Many gay titles peppered the paperback racks in the years following, as the new Homophile movement grew in the U.S. and homosexual law reform started to be discussed in Britain. The 1950's also saw a profusion of lesbian pulp novels (now documented by Jaye Zimet's Strange Sisters), and in the Sixties, erotic gay paperback fiction became more widely available.

The American public was first introduced to the realities of homosexual life not by radio or TV, nor by The New York Times or the Mattachine Society, but by the paperback revolution that brought gay and lesbian books into every American town. In 1966 there was even a book called The Homosexual Explosion.

These new "mass market" paperbacks were not sold by reviews,

literary critics, librarians or educators. Produced in standard 7" x 4 1/4"

format and displayed on stout, rotating wire racks or face out on store

shelves, their covers served as their advertisements. Many pulpy reprints of

Zola's Nana and Balzac's Droll Stories were sold by garish cover

illustrations of well-endowed females bursting out of their bodices. Then as

now, living authors had no more control than dead ones over cover art.

Sometimes, gay novels were given hetero covers; James Colton's Lost on

Twilight Road (National Library, 1964) showed a half-naked woman

ripping the clothes off a stunned-looking man. Only the code word "twilight" in

the title suggests what it's all about. But most publishers soon abandoned this

approach. Paperback covers were more explicit, sometimes more attractive, and

often better designed than their hardcover equivalents.

These new "mass market" paperbacks were not sold by reviews,

literary critics, librarians or educators. Produced in standard 7" x 4 1/4"

format and displayed on stout, rotating wire racks or face out on store

shelves, their covers served as their advertisements. Many pulpy reprints of

Zola's Nana and Balzac's Droll Stories were sold by garish cover

illustrations of well-endowed females bursting out of their bodices. Then as

now, living authors had no more control than dead ones over cover art.

Sometimes, gay novels were given hetero covers; James Colton's Lost on

Twilight Road (National Library, 1964) showed a half-naked woman

ripping the clothes off a stunned-looking man. Only the code word "twilight" in

the title suggests what it's all about. But most publishers soon abandoned this

approach. Paperback covers were more explicit, sometimes more attractive, and

often better designed than their hardcover equivalents.

Gay paperbacks might reflect the prejudices of the day in either text or cover - or both. Or they might not. Either way, they popularized the subject by disseminating millions of images of homosexuals. These images were at once public and private, because a book, especially a paperback designed to be carried in the pocket (one of the leading publishers was Pocket Books), is first seen publicly on the drugstore rack, and later looked at and read in private or even in secret, often at night. Many dreamboys had their origins in paperback cover art.

So began the demythologizing of that chimaera The Homosexual. Paperbacks gave homosexuality enormous public visibility at a time when public images of gay men were rare, ugly and frightening. At as little as 35c, paperbacks were priced to appeal to a broad public, and gay paperbacks were no exception. Today, those paperbacks that have not fallen apart or been discarded have become highly collectible as interest in their cover art and social significance increases.

***

Perhaps the

most notorious of the gay novels of the Forties and Fifties was Gore Vidal's

The City and the Pillar, which so unnerved The New York

Times it refused even to print the publisher's ads. Nonetheless, this story

of an itinerant tennis player who eventually murders his boyhood friend did

well in paperback as its numerous editions incorporated a series of textual

revisions by the author. The 1950 Signet edition bore a cover painting by the

best of the paperback artists, James Avati. It showed a petulant woman in a

tasteful, low-cut dress looking down at a pensive young man. This motif of the

Concerned Woman was frequently used: Dean Douglas' Man Divided (Gold

Medal, 1954) and Dyson Taylor's Bitter Love (Pyramid, 1957) were among

many whose covers showed eye-catching dames displaying concern for depressed

looking fellows. The prototype was an early, undated paperback reprint of

Richard Meeker's 1933 novel Better Angel; retitled Torment, it

showed a woman reaching out to a man in a suit who appears to be hiding his

head in the curtains.

Perhaps the

most notorious of the gay novels of the Forties and Fifties was Gore Vidal's

The City and the Pillar, which so unnerved The New York

Times it refused even to print the publisher's ads. Nonetheless, this story

of an itinerant tennis player who eventually murders his boyhood friend did

well in paperback as its numerous editions incorporated a series of textual

revisions by the author. The 1950 Signet edition bore a cover painting by the

best of the paperback artists, James Avati. It showed a petulant woman in a

tasteful, low-cut dress looking down at a pensive young man. This motif of the

Concerned Woman was frequently used: Dean Douglas' Man Divided (Gold

Medal, 1954) and Dyson Taylor's Bitter Love (Pyramid, 1957) were among

many whose covers showed eye-catching dames displaying concern for depressed

looking fellows. The prototype was an early, undated paperback reprint of

Richard Meeker's 1933 novel Better Angel; retitled Torment, it

showed a woman reaching out to a man in a suit who appears to be hiding his

head in the curtains.

For some reason, Signet dropped Avati's painting from its 1955

edition of The City and the Pillar and replaced it with a cropped

version of a picture it had used on a gay novel from 1952, Fritz Peters'

Finistère. On Peters' novel ("A Powerful Novel of a Tragic

Love...doomed from the first!") the male half of a straight couple necking on a

sofa looks out onto a balcony where a somewhat green-faced youth leans over a

railing. On the version adapted for the Vidal cover ("A Masterful Story of a

Lonely Search") only the green youth remains. The couple have been replaced by

a quotation from a review.

For some reason, Signet dropped Avati's painting from its 1955

edition of The City and the Pillar and replaced it with a cropped

version of a picture it had used on a gay novel from 1952, Fritz Peters'

Finistère. On Peters' novel ("A Powerful Novel of a Tragic

Love...doomed from the first!") the male half of a straight couple necking on a

sofa looks out onto a balcony where a somewhat green-faced youth leans over a

railing. On the version adapted for the Vidal cover ("A Masterful Story of a

Lonely Search") only the green youth remains. The couple have been replaced by

a quotation from a review.

The Concerned Woman is only one of a number of frequently recurring gay cover motifs. The Looming Presence is another: a young man appears in the foreground, sometimes with a woman. Another (usually older) man looms or lurks menacingly in the background - suggesting a homosexuality that is predatory rather than reciprocal. For Signet's 1959 edition of Giovanni's Room, Daniel Schwartz cleverly brought the Looming Presence out of the shadows and into the foreground, to be revealed as the tall, dark and handsome Giovanni, with his thumb in his belt, and very large feet. An unmade bed and a half-finished bottle of liquor lie behind the doorway.

A copy of Giovanni's Room appeared as a prop

in the Jeremy Thorpe murder conspiracy case in 1979. Thorpe, leader of the

British Liberal Party, stood accused of conspiring to have a talkative

ex-boyfriend disposed of. Thorpe was acquitted, after a somewhat campy trial.

His loan of a copy of Baldwin's novel to the alleged victim, and their

subsequent night together, were detailed in court. Would the book gently tossed

on the bed have been a dusty old hardcover without its jacket that had been

hanging around Thorpe's library for years and trotted out on appropriate

occasions? Or would the recently reissued Corgi edition be a more likely

candidate? It shows two scantily dressed young men, one looking at the other,

who is looking away. The Corgi seems somehow appropriate.

A copy of Giovanni's Room appeared as a prop

in the Jeremy Thorpe murder conspiracy case in 1979. Thorpe, leader of the

British Liberal Party, stood accused of conspiring to have a talkative

ex-boyfriend disposed of. Thorpe was acquitted, after a somewhat campy trial.

His loan of a copy of Baldwin's novel to the alleged victim, and their

subsequent night together, were detailed in court. Would the book gently tossed

on the bed have been a dusty old hardcover without its jacket that had been

hanging around Thorpe's library for years and trotted out on appropriate

occasions? Or would the recently reissued Corgi edition be a more likely

candidate? It shows two scantily dressed young men, one looking at the other,

who is looking away. The Corgi seems somehow appropriate.

Looking Away, as it happens, is one of the most frequent of repeated motifs on gay paperback covers. One man looks at another, but the second looks away, toward a woman or at the reader or off into space, never returning the longing gaze. This motif lasted several decades, cropping up again and again on titles that included Finistère in the Fifties, Sean O'Shea's Whisper and Ben Travis' The Strange Ones in the Sixties and Patricia Nell Warren's The Front Runner in the Seventies. Pyramid's 1963 edition of Eric Jourdan's steamy tragedy Les Mauvais Anges (which it retitled Two) provided an additional suggestive touch. The cover painting of two boys shows the darker of the two - the predator presumably - eyeing the other and smoking a cigarette, while the blond - gay but still a virgin - is pretending to be fascinated by a daisy.

An improvement on Looking Away was the Cruising motif. Here one man looks at the other who turns, perhaps about to exchange glances. Images of male couples actually Face to Face were rare. Avon's 1971 paperback reprint of Gordon Merrick's The Lord Won't Mind was quite revolutionary; a romantic realist painting depicted two handsome blond men Face to Face, reaching out as though about to hold hands, almost touching. Men embracing or holding hands were seldom shown, and men kissing one another remained taboo. One exception was Adonis' 1975 title Stud Joint by Ross Helden, which shows a handsome sailor in the foreground, and, through an open saloon-type door, a male couple kissing in the back room. The kiss prominently displayed on Avon's 1979 edition of Paul Monette's Taking Care of Mrs. Carroll ("A moving celebration of gay love") furthered the paperback publisher's reputation as a pioneer in gay paperback cover design.

|

|

|

The rise of the Hippie movement in the mid- to late Sixties was reflected only slightly in the gay paperbacks of the time. Dick Dale's The Price of Pansies (Phenix, 1968) came adorned with a reclining teenager with a pansy on his crotch and a For Sale sign: "He was a gay flower child!" And the cover of Bert Shrader's Gay Stud's Trip, published by French Line the same year, attempted an approximation of the psychedelic style in its red and blue drawing of two naked guys sharing a cigarette. But truckers, bikers and servicemen seem to have remained more popular than hippies - or the well-groomed gay winos amusingly depicted on Gene (or Jean, the publishers weren't sure) North's Skid Row Sweetie.

In the Sixties and Seventies, movie and TV tie-ins began to appear, sometimes screenplays but more often novelizations of films or TV shows, displaying photos of the stars and sometimes including several pages of (usually black & white) stills. One of the first of these was Victim, William Drummond's 1961 Corgi novelization of a powerful Dirk Bogarde film about a blackmailed gay lawyer. Later tie-in titles included Sunday Bloody Sunday, Fame, An Early Frost, Making Love and that gay movie for straight people (or was it a straight movie for gay people?) Can't Stop the Music.

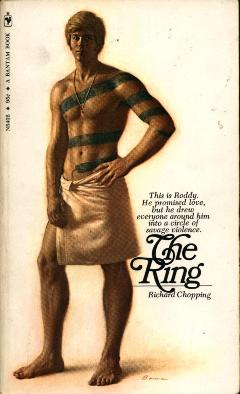

The solitary Handsome Young Man or Pretty Boy was of course a

staple of gay cover design, for both erotic and literary titles. Some of the

most stunning were featured on James Purdy's Eustace Chisholm and the Works

("The Sensational Novel of Perverse Love," Bantam, 1968), Angus Stewart's

school romance Sandel (Panther, 1970), Jonathan Strong's story

collection Tike (Avon, 1970), Richard Amory's detective story Frost

(Olympia, 1971) and Jonathan Melburn's Billy Stud (Greenleaf/Adonis,

1975). On Andre Dubus' The Lieutenant (Dell, 1968) the pretty, shirtless

enlisted man is joined by an older, crew-cut martinet type with a swagger

stick, presumably the Lieutenant of the title. Another spectacular pretty boy

is discreetly but enticingly nude on John Rechy's Numbers (Grove/Black

Cat, 1968).

The solitary Handsome Young Man or Pretty Boy was of course a

staple of gay cover design, for both erotic and literary titles. Some of the

most stunning were featured on James Purdy's Eustace Chisholm and the Works

("The Sensational Novel of Perverse Love," Bantam, 1968), Angus Stewart's

school romance Sandel (Panther, 1970), Jonathan Strong's story

collection Tike (Avon, 1970), Richard Amory's detective story Frost

(Olympia, 1971) and Jonathan Melburn's Billy Stud (Greenleaf/Adonis,

1975). On Andre Dubus' The Lieutenant (Dell, 1968) the pretty, shirtless

enlisted man is joined by an older, crew-cut martinet type with a swagger

stick, presumably the Lieutenant of the title. Another spectacular pretty boy

is discreetly but enticingly nude on John Rechy's Numbers (Grove/Black

Cat, 1968).

Occasionally a symbolic approach was favored. Signet's 1966 edition of Sanford Friedman's gay novel of the Korean war, Totempole, featured a salamander with its tail cut off, implying a perhaps unsuccessful attempt at castration. But as the Gay Liberation era approached, these negative assumptions began to ebb and fewer novels ended in tragic death. Kennedy replaced Eisenhower in the U.S., the Swinging Sixties got under way in Britain, and things started to loosen up. A number of important censorship trials (including that of the paperbound Howl) overturned the outright ban on published erotic writing. The golden age of gay erotica began.

***

Some early gay erotic novels had been published by outfits on

the cusp of legality like the Guild Press, which for a time was operated from a

mental institution where its eccentric proprietor was hiding from the police!

But as censorship slackened, porn publishers proliferated. Most authors of gay

erotica used pen names ("Billy Farout" for example was the poet William Barber;

"James Colton" later made his reputation as Joseph Hansen, author of the Dave

Brandsetter detective novels) but a few like the Englishman C.J. Bradbury

Robinson used their own names. One of the

first, and best, writers in the field was Samuel Steward whose "Phil Andros"

stories were published by Greenleaf Classics and Frenchy's Gay Line. Piracy was

sometimes a problem for such legally dubious material. Steward's San

Francisco Hustler was ripped off by Cameo Library who reprinted it as

Gay in San Francisco by "Biff Thomas" - though the fact that the pirate

edition included a chapter excised from the original edition raised unanswered

questions.

Some early gay erotic novels had been published by outfits on

the cusp of legality like the Guild Press, which for a time was operated from a

mental institution where its eccentric proprietor was hiding from the police!

But as censorship slackened, porn publishers proliferated. Most authors of gay

erotica used pen names ("Billy Farout" for example was the poet William Barber;

"James Colton" later made his reputation as Joseph Hansen, author of the Dave

Brandsetter detective novels) but a few like the Englishman C.J. Bradbury

Robinson used their own names. One of the

first, and best, writers in the field was Samuel Steward whose "Phil Andros"

stories were published by Greenleaf Classics and Frenchy's Gay Line. Piracy was

sometimes a problem for such legally dubious material. Steward's San

Francisco Hustler was ripped off by Cameo Library who reprinted it as

Gay in San Francisco by "Biff Thomas" - though the fact that the pirate

edition included a chapter excised from the original edition raised unanswered

questions.

While Steward/Andros dealt with rough trade, hustlers and S/M, another writer of Sixties erotica, Carl Corley, specialized in romantic stories of boys from the country. He adopted a distinctive camp/kitsch style to illustrated his own covers, which bore titles like Cast a Wistful Eye. The well-known French publisher Maurice Girodias issued a number of English-language gay books which made their way to America. An edition of The Young & Evil, the classic novel of New York gay life in the Thirties by Parker Tyler and Charles Henri Ford, featured a wrap-around cover with a delicious black-&-white photo of a reclining near-naked young man. Later Girodias' U.S. imprint issued the non-fiction gay guide The Homosexual Handbook, around the time of the Stonewall rebellion. Threatened retribution by F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover and conservative columnist William F. Buckley, Jr. led to their names being removed from the "grapevine line-up" for the book's second edition. Girodias took great care with the appearance of his books, whose covers were often elegantly conservative in appearance.

The leading publisher of gay erotica in the Sixties and

Seventies was Phenix/Greenleaf Classics whose later productions adopted a

distinctive H-format cover style. It was Greenleaf who in 1970 issued the first

post-Stonewall anthology of contemporary gay literature, E.V. Griffith's In

Homage to Priapus. They were also responsible for Richard Amory's 1966

Song of the Loon, a "gay pastoral" about love and sex between white men

and red in the American wilderness. This Leatherstocking tale with the sex put

back in became the most famous of all gay erotic novels, at least prior to the

arrival of the unbearable Mr. Benson fourteen years later. Song of

the Loon's wrap-around cover design avoided both the old "people of the

shadows" stereotype and the blatantly sexual approach that would become

standard for later gay porn. It showed a bearded white man in buckskins

kneeling by a young, flute-playing Indian against a backdrop of mountains,

reeds and white willows.

The leading publisher of gay erotica in the Sixties and

Seventies was Phenix/Greenleaf Classics whose later productions adopted a

distinctive H-format cover style. It was Greenleaf who in 1970 issued the first

post-Stonewall anthology of contemporary gay literature, E.V. Griffith's In

Homage to Priapus. They were also responsible for Richard Amory's 1966

Song of the Loon, a "gay pastoral" about love and sex between white men

and red in the American wilderness. This Leatherstocking tale with the sex put

back in became the most famous of all gay erotic novels, at least prior to the

arrival of the unbearable Mr. Benson fourteen years later. Song of

the Loon's wrap-around cover design avoided both the old "people of the

shadows" stereotype and the blatantly sexual approach that would become

standard for later gay porn. It showed a bearded white man in buckskins

kneeling by a young, flute-playing Indian against a backdrop of mountains,

reeds and white willows.

The book was such a hit it even inspired a paperback parody called

Fruit of the Loon.  There were also several sequels and a

movie. The popularity of the Amory books indicated a mass market eager for gay

romance and semi-retired novelist Gordon Merrick stepped into the breach.

The Lord Won't Mind and its various follow-ups featured soap-opera plots

and gay heroes gifted with spectacular endowments both physical and financial.

All but the first of these were published as paperback originals, and it fell

to them to break completely the Looking Away fixation. Avon's matching,

romantic-realist covers for the series featuring men reaching out to each other

or showing affection were displayed in supermarket bookracks all over America.

There were also several sequels and a

movie. The popularity of the Amory books indicated a mass market eager for gay

romance and semi-retired novelist Gordon Merrick stepped into the breach.

The Lord Won't Mind and its various follow-ups featured soap-opera plots

and gay heroes gifted with spectacular endowments both physical and financial.

All but the first of these were published as paperback originals, and it fell

to them to break completely the Looking Away fixation. Avon's matching,

romantic-realist covers for the series featuring men reaching out to each other

or showing affection were displayed in supermarket bookracks all over America.

With even a respectable house like Avon venturing into soft-core gay erotica, a number of companies came along to rival Greenleaf's hard-core efforts. Surree House's HIS 69 series featured drawings of near-naked boy-next-door types, usually in pairs. Rough Trade's leather and S/M titles were distinguished by the publisher's trademark black and orange covers which often incorporated the drawings of the well-known illustrator Rex.

Another of the Seventies erotica publishers was Blueboy Library, associated with the then-popular magazine of the same name. It was Blueboy Library that published a number of titles by John Ironstone which combined erotica with gay political themes. The cover of Ironstone's I Am Proud To Be Gay Now I Want To Be Free showed gay lib banners vying with Anita Bryant placards outside an orange juice stand.

But by the early Eighties, the tide had begun to turn for gay

paperback porn. A changing legal and economic climate led to the demise of the

leading Seventies publishers. AIDS altered sexual attitudes and more

gay-oriented novels were published by commercial presses. When Larry Kramer's

Faggots appeared in paperback, you could choose from several cover

colors, perhaps to coordinate with your living room decor. But in the 1990's

Masquerade Books' Badboy and Hard Candy editions took over where Greenleaf and

the others had left off, and began publishing reprints and more literary books

as well.

But by the early Eighties, the tide had begun to turn for gay

paperback porn. A changing legal and economic climate led to the demise of the

leading Seventies publishers. AIDS altered sexual attitudes and more

gay-oriented novels were published by commercial presses. When Larry Kramer's

Faggots appeared in paperback, you could choose from several cover

colors, perhaps to coordinate with your living room decor. But in the 1990's

Masquerade Books' Badboy and Hard Candy editions took over where Greenleaf and

the others had left off, and began publishing reprints and more literary books

as well.

Nowadays more gay books are published in the larger Trade Paperback format (approximately 8 ½" x 5 ½") though some still appear as Mass Market paperbacks. But some of the old gay paperbacks have survived and are still to be found cheaply in junk shops and secondhand bookstores. They are starting to be recognized as important cultural artefacts, their changing images of gay men faithfully documenting the evolution of popular views and beliefs. A first edition of Carl Corley's The Purple Ring now fetches $100, and the price for a first edition Song of the Loon is climbing even higher! Savored when they appeared, often taken for granted or discarded later, gay paperbacks are beginning to acquire a nostalgic, Antiques Roadshow, "I Found It in the Attic" glamour. And they retain all their initial pulpy Reach Out And Buy Me appeal..

Gay paperbacks have been part of my own life since before I walked out of a dime store listening to my heart beat, with a copy of Two in my pocket (together with a Signet Classics Walden - one never bought only a gay book!). I was 18. And years later, wandering around Greenwich Village at night, I usually had a paperback in my jeans or coat. (I liked - or rather, enjoyed and admired - City of Night, but I thought Mr Benson was a jerk.)

Let's leave with a pair of very different quotes, one suggestively macabre, the other combining the joys of the orgy with the pure sentiment of the pastoral romance. Both are from gay books published as paperback originals.

The first sentence of William Talsman's The Gaudy Image (Olympia Press, 1958): "I regret that I shall be unable to spend my eternity listening to the rain as it falls upon my casket roof."

And the ending of Jack Evans' The Randy Young Runaway, published, undated - with explicit color photos - by a nameless company: "Come flew in every direction, reaching as high as their faces. They fucked and fucked, and afterwards they all felt like brothers. When it was over they headed for the river to wash off. Then they all sprawled out on the ground for a quick snooze, leaving only Ted and Hank sitting together on the bank. 'I love you, you know, Ted,' Hank suddenly blurted out... They held hands without saying a word; what else was there to say?"

***