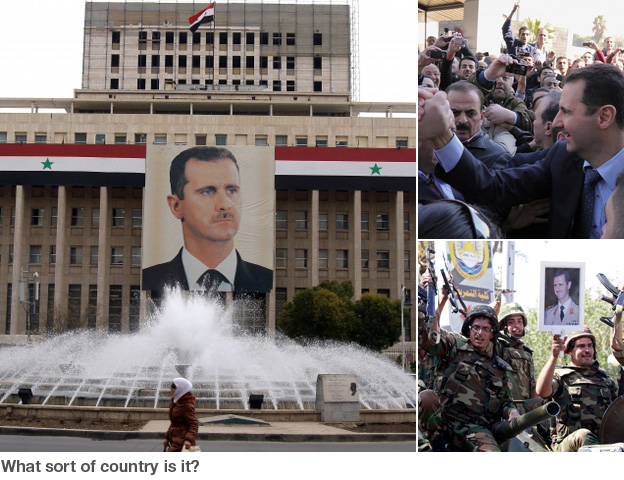

Syria's year of protest and insurrection

The Assads appear to believe they can weather the storm

The Assads appear to believe they can weather the storm

It is a year since President Bashar al-Assad's men responded to peaceful demonstrations in the southern Syrian town of Deraa with automatic weapons.

A few weeks before he had blithely told a reporter from the Wall Street Journal that Syria would not catch the virus of revolution that was tearing through the Arab world.

The reason, he said, was that the president shared an ideology with the people, which would give Syria immunity.

The irony of the last 12 months is that Mr Assad was not wrong about the genuine legitimacy he had among much of the population. Many of those who did not like the repressive Syrian system listened to his promises of reform and hoped he would keep them.

Syrians liked the way that he stood up to Israel and the West. He had considerable reflected glory from his support of the leader of Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hassan Nasrallah, who was the rock star of Arab politics after he took on Israel in 2006.

But that did not mean that large sections of the population would accept his explanation for what was happening, as demonstrations spread after the first killings of unarmed protesters in Deraa a year ago.

Riding out stormMr Assad said Syria was fighting for its life against a violent conspiracy directed from abroad by foreigners. Too many people knew too much about life in one of the tightest police states in the Middle East to believe this.

The Syrian army is retaking city after city, but rebels are retreating

The Syrian army is retaking city after city, but rebels are retreating

A year on, the Assad regime is facing an armed insurrection. The regime has powerful military forces, which are being used to drive armed rebels out of important centres of revolt.

They started in the Damascus suburbs, moved on to Homs, the Idlib and now seem to be concentrating on Deraa again.

But the thing about asymmetric warfare - the fight of the weak against the strong - is that it is not about pitched battles.

For the weaker side, keeping going matters above all. If the Gulf Arabs keep their promise to supply arms to the rebels then the uprising will increase in intensity.

So far President Assad is riding out the storm, and appears to believe that he can win. As well as the military, he has genuine support from his own Alawite community, and other Syrian minorities, including Christians, who fear what the consequences of a violent change of power.

Russian irritationAnother reason for the regime's continuing cohesion is that key jobs are either in the hands of members of his family - or other trusted Alawites - who are not likely to defect.

And Mr Assad has Russia to protect him at the UN Security Council.

The Russians, perhaps reflecting their isolation on Syria, have displayed some public irritation with the regime in the last few days.

But they value their alliance with Syria, which is Russia's only real friend in the region. Mosocw has a listening post and a naval base in Syria, and does not want to lose them.

International attention is now on the mission by the UN-Arab League envoy, Kofi Annan.

He is trying to stop the killing by starting a political dialogue involving all sides. If his mission fails, and civilians continue to die, there will be another round of pressure for direct military intervention by foreign powers.

The Syrian government has been trying to suppress an uprising inspired by events in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. The UN says thousands have been killed in the crackdown, and that many more have been detained and displaced. The Syrian government says hundreds of security forces personnel have also died combating "armed terrorist gangs".

The Syrian government has been trying to suppress an uprising inspired by events in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. The UN says thousands have been killed in the crackdown, and that many more have been detained and displaced. The Syrian government says hundreds of security forces personnel have also died combating "armed terrorist gangs".

The family of President Bashar al-Assad has been in power since his father, Hafez, took over in a coup in 1970. The country underwent some liberalisation after Bashar became president in 2000, but the pace of change soon slowed, if not reversed. Critics are imprisoned, domestic media are tightly controlled, and economic policies often benefit the elite. The country's human rights record is among the worst in the world.

The family of President Bashar al-Assad has been in power since his father, Hafez, took over in a coup in 1970. The country underwent some liberalisation after Bashar became president in 2000, but the pace of change soon slowed, if not reversed. Critics are imprisoned, domestic media are tightly controlled, and economic policies often benefit the elite. The country's human rights record is among the worst in the world.

Syria is a country of 21 million people with a Sunni Muslim majority (74%) and significant minorities of Alawites - the Shia heterodox sect to which Mr Assad belongs - and Christians. Mr Assad promotes a secular identity for the country, but he has concentrated power in the hands of family and other Alawites. Protests have generally been biggest in Sunni-dominated areas.

Syria is a country of 21 million people with a Sunni Muslim majority (74%) and significant minorities of Alawites - the Shia heterodox sect to which Mr Assad belongs - and Christians. Mr Assad promotes a secular identity for the country, but he has concentrated power in the hands of family and other Alawites. Protests have generally been biggest in Sunni-dominated areas.

Under the sanctions imposed by the Arab League, US and EU, Syria's two most vital sectors, tourism and oil, have ground to a halt in recent months. The IMF says Syria's economy contracted by 2% in 2011, while the value of the Syrian pound has crashed. Unemployment is high, electricity cuts trouble Damascus, and critical products like heating oil and staples like milk powder are becoming scarce.

Under the sanctions imposed by the Arab League, US and EU, Syria's two most vital sectors, tourism and oil, have ground to a halt in recent months. The IMF says Syria's economy contracted by 2% in 2011, while the value of the Syrian pound has crashed. Unemployment is high, electricity cuts trouble Damascus, and critical products like heating oil and staples like milk powder are becoming scarce.

Pro-democracy protests erupted in March 2011 after the arrest and torture of a group of teenagers who had painted revolutionary slogans on walls at their school in the southern city of Deraa. Security forces opened fire during a march against the arrests, killing four. The next day, the authorities shot at mourners at the victims' funerals, killing another person. People began demanding the overthrow of Mr Assad.

Pro-democracy protests erupted in March 2011 after the arrest and torture of a group of teenagers who had painted revolutionary slogans on walls at their school in the southern city of Deraa. Security forces opened fire during a march against the arrests, killing four. The next day, the authorities shot at mourners at the victims' funerals, killing another person. People began demanding the overthrow of Mr Assad.

The government has tried to deal with the situation with a combination of minor concessions and force. President Assad ended the 48-year-long state of emergency and introduced a new constitution offering multi-party elections. But at the same time, the authorities have continued to use violence against unarmed protesters, and some cities, like Homs, have suffered weeks of intense bombardment.

The government has tried to deal with the situation with a combination of minor concessions and force. President Assad ended the 48-year-long state of emergency and introduced a new constitution offering multi-party elections. But at the same time, the authorities have continued to use violence against unarmed protesters, and some cities, like Homs, have suffered weeks of intense bombardment.

The opposition is deeply divided. Several groups formed a coalition, the Syrian National Council (SNC), but it is dominated by the Sunni community and exiled dissidents. The SNC disagrees with the National Co-ordination Committee (NCC) on the questions of talks with the government and foreign intervention, and has found it difficult to work with the Free Syrian Army - army defectors seeking to topple Mr Assad by force.

The opposition is deeply divided. Several groups formed a coalition, the Syrian National Council (SNC), but it is dominated by the Sunni community and exiled dissidents. The SNC disagrees with the National Co-ordination Committee (NCC) on the questions of talks with the government and foreign intervention, and has found it difficult to work with the Free Syrian Army - army defectors seeking to topple Mr Assad by force.

International pressure on the Syrian government has been intensifying. It has been suspended from the Arab League, while the EU and the US have imposed sanctions. However, there has been no agreement on a UN Security Council resolution calling for an end to violence. Although military intervention has been ruled out by Western nations, there are increasing calls to arm the opposition.

International pressure on the Syrian government has been intensifying. It has been suspended from the Arab League, while the EU and the US have imposed sanctions. However, there has been no agreement on a UN Security Council resolution calling for an end to violence. Although military intervention has been ruled out by Western nations, there are increasing calls to arm the opposition.

Correspondents say a peaceful solution seems unlikely. Syria's leadership seems intent on crushing resistance and most of the opposition will only accept an end to the regime. Some believe the expected collapse of Syria's currency and an inability to pay salaries may be the leadership's downfall. There are fears, though, that the resulting chaos would be long-lasting and create a wider conflict.

Correspondents say a peaceful solution seems unlikely. Syria's leadership seems intent on crushing resistance and most of the opposition will only accept an end to the regime. Some believe the expected collapse of Syria's currency and an inability to pay salaries may be the leadership's downfall. There are fears, though, that the resulting chaos would be long-lasting and create a wider conflict.

Divisions laid bare

Divisions laid bare Syria's fragile ceasefire holding

Syria's fragile ceasefire holding Florida gunman appears in court

Florida gunman appears in court Child labour exposed

Child labour exposed Amped up

Amped up Battleground states

Battleground states Will you?

Will you?  Going gourmet

Going gourmet  Click

Click