Composing Graphic Narratives

355:402:02

Fall 2008

Instructor: Jonathan Bass

Thursday 1:10-4:10 PM

Index Number: 14468

For a short description of the class, see the Writing Program's 402 index page.

It's Not Over Yet

UPDATE to submitting final work (Dec. 14). Work should be on Scribd and in your Drop Box on the 402 Sakai site by 6 PM on Monday, Dec. 15. Also, despite what was said below, only one member of the group needs to post (1) the intro material and (2) the contents spread.

Why on Scribd and Sakai? Because it's easier for me to view your work on Scribd but easier for me to keep track of what comes in on Sakai.

Note, however, that we might run out of space on Sakai. If that happens, let me know of the problem by email.

If you have any other questions, send me an email. Also, if you have not submitted your time comic by this point, you might want to contact me, especially if you still intend to submit one.

Final Project

Due dates and formats for the Final Project:

- Monday, Dec. 15 A high-quality digital copy of the contents page, intro, and your individual story on Scribd.

- Monday, Dec. 15 A high-quality digital copy of the contents page, intro, and your individual story in the dropbox on Sakai (but check back on Sunday, Dec. 14, for possible change to this. I need to see how much space I can make for us on the Sakai).

- Wednesday, Dec. 17 A printed/photocopied version of your story/chapter in my mailbox in Murray Hall by 12 PM/Noon.

Note: Each student is responsible for submitting separately their own story/chapter and a copy of the contents page and intro on Scribd and Sakai. You do not each have to submit the complete anthology.

Final Office Hour

Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2.30-3.30 PM. Loree 010. Stop by for final grades and comments. Otherwise send me an email clearly requesting that I send your grade by email.

topWeek Fourteen

In class

Work Due

- One-page story synopsis (printed), including introductory paragraph that explains relation of your story to the anthology's theme.

- Panel-by-panel script (printed) or thumbnails (photocopy or printed scan) for at least first two pages of story.

- Character designs for the anthology's host and for at least two main characters (human, animal, alien, supernatural, metaphysical, or inanimate). Bring in both drawn and scanned (600 ppi tiff) versions of your sketches/designs.

- Ideas and designs for the 2-page collaborative table of contents and credits. Note: The next class is the last, thus the last chance to work in class together on this part of the project.

Of Interest

My classes for Spring 2009.

More on Digital File Formats for comics (Sean Kleefeld).

Final Project

Work on the Final Project.

Homework

Complete the Final Project.

You'll need to submit your work in three versions:

- A printed/photocopied version of your story/chapter in my mailbox in Murray Hall

- A high-quality digital copy of the contents page, intro, and your individual story on Scribd

- A high-quality digital copy of the contents page, intro, and your individual story in the drop box on Sakai

Week Twelve

In class

Work Due

Multiple Time(s) Comic.

In Memoriam

Guy Peellaert: Examples of his Comics; hommage to his style (Christophe Blain).

Final Project

You'll spend much of today's class planning and starting to draw/design the Final Project. If necessary, you can spend some of this time formatting your Time(s) Comic.

More Examples for Discussion

These were left over from last week:

- Bryan Talbot, Alice in Sunderland

- Lauren McCubbin, Harvest Gypsy: Quasi-informational; look at the use of the map in the images.

- Lardfork, Experimental Comics: Use of transformed photographs, screenshoots, etc.

- ???, History of LSD

- Chris Ware, Cinefamily cover (on film director Yasujiro Ozu)

- Jim Shaw: The Temptation of Doubting Olsen (1990); The Girls in Billy's Class #1 (1986).

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Edward Tufte, Envisioning Information (browse on Sakai).

Final Project

A mix of things are due for the next class:

- One-page story synopsis (printed), including introductory paragraph that explains relation of your story to the anthology's theme.

- Panel-by-panel script (printed) or thumbnails (photocopy or printed scan) for at least first two pages of story.

- Character designs for the anthology's host and for at least two main characters (human, animal, alien, supernatural, metaphysical, or inanimate). Bring in both drawn and scanned (600 ppi tiff) versions of your sketches/designs.

- Ideas and designs for the 2-page collaborative table of contents and credits. Note: The next class is the last, thus the last chance to work in class together on this part of the project.

Week Eleven

In class

Work Due

As discussed in the last class: the new due date for the Time(s) Comic is next week, Nov. 20. However, you should have made visible progress on the comic by this class. Bring scans and/or original pages to class for review and discussion.

Of Interest

Mac specific comics stuff (promotional): Featuring Mike Mignola

Minute Movie and Interview Comics Review

We'll complete the review/discussion of the Minute Movie comics and start looking at your Interview Comics.

Three Informational Comics by Josh Neufeld

I've also linked these under the reading for next week but we'll preview them in class.

- Josh Neufeld, "Origin of a Planet Keeper"

- Josh Neufeld, "Travel Tips #2: Rolling"

- Josh Neufeld (and his mom, Martha Rosler of Mason Gross), "Scenes From an Illicit War: From Planet Invisible"

Comics and Diagrams

First let's glance previewingly at Edward Tufte on Links and Causal Arrows and Mapped Pictures/Annotated Images. (This is part of the reading for next week.)

Next some non-comics examples, one you might recall from last week:

Finally, some comics examples:

- Chris Ware, Building Stories (1)

- Chris Ware, Building Stories (2a)

- Chris Ware, Building Stories (2b)

- Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan (poster?)

- Dan Dare Cut-Away Diagrams

- Dan Zettwoch, "Young Abe Lincoln's Log Fort"

- Dan Zettwoch, Postal Peril

- Dan Zettwoch, Gross Anatomy

Final Project

Introducing the Final Project.

More Examples for Discussion

- Bryan Talbot, Alice in Sunderland

- Lauren McCubbin, Harvest Gypsy: Quasi-informational; look at the use of the map in the images.

- Lardfork, Experimental Comics: Use of transformed photographs, screenshoots, etc.

Timescale Comics Project

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Abel and Madden, chaps. 11 & 12.

- Edward Tufte on Links and Causal Arrows and Mapped Pictures/Annotated Images.

- Scott McCloud, From Page to Screen (educational/informational comic).

- More reading on page layout: "Can't I Cantilever? Yes, you can!" (with lots of pictures)

Comics in Brunetti:

- A clinical piece by Daniel Clowes: "Gynecology" (375)

- And Dan Raeburn on Clowes (397)

Linked Comics (mainly informational, fact-based):

- Eddie Campbell, French Holiday (on Sakai)

- Dan Zettwoch, Deadlock

- Lauren McCubbin, Harvest Gypsy: Quasi-informational; look at the use of the map in the images

- Various artists, Nature Comics (PDF)

- Josh Neufeld, "Origin of a Planet Keeper"

- Josh Neufeld, "Travel Tips #2: Rolling"

- Josh Neufeld (and his mom, Martha Rosler of Mason Gross), "Scenes From an Illicit War: From Planet Invisible"

- Josh Neufeld, A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge

Timescale Comics Project

Finish work on the project. The final version should be 4-8 pages. The majority of the pages should have at least five panels. If your pages are going to have fewer panels, aim for more pages and disucss your layout ideas with me.

Week Ten

In class

Work Due

Script/plot outline/breakdowns for you Multiple Times Comic (as I'm calling it today). Bring two printed copies, one for peer review and discussion and one to turn in.

Initial work on the comic. Bring scans/electronic versions of at least some of your work for in-class review and a possible exercise.

Minute Movie and Interview Comics Review

We'll complete the review/discussion of the Minute Movie comics and start looking at your Interveiw Comics.

Presentation

Natalie and Gissele will present on McCloud, chapter 8.

Timescale Comics Project

Further work on this comic.

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 9.

Comics in Brunetti:

- Burns, from Curse of the Molemen (118)

Linked Comics:

Timescale Comics Project

Update: As discussed in the class, the due date for the project has been extended to Nov. 20. However, we'll begin working on a new project next week as well.

The final version of the Time(s) Comic should be 4-8 pages. The majority of the pages should have at least five panels. If your pages are going to have fewer panels, aim for more pages and disucss your layout ideas with me.

Week Nine

In class

Work Due

Zimmerli drawings, photos, notes, etc., based on at least two works on which to base panels in the Time Project. Bring these to class for refrence and discussion.

Of Interest

The first of two Mike Mignola Hellboy comics: Hellboy: In the Chapel of Moloch (excerpt, PDF). I link to this one mainly because of the Goya reference on page 4.

Drawing Alan's War: Video.

Coloring Your Comics

Here are some tutorials for coloring comics using Photoshop.

- Zander Cannon, Tips and Tricks: Computer Coloring

- Zander Cannon, Tips and Tricks: Coloring Comics to Look Old

More on Time and Narrative in Comics

We didn't get to this last week. So let's take a look today.

- R. Crumb, "A Short History of America"

- Richard McGuire, "Here"

- Kevin Huizenga, "The Sunset" (p. 285)

- Jaime Hernandez, "Flies on the Ceiling": p. 201, p. 202, p. 203.

- Alan Moore and Rick Vietch, Greyshirt in "How Things Work Out" (Tomorrow Stories #2, 1999; now on Sakai)

- Mike Mignola, Hellboy in "Doctor Carp's Experiment" (on Sakai)

Timescale Comics Project (Revised Description)

Tell a comics story in five or more pages using words, pictures, graphic devices, page design, etc.

- Story should have a narrator, although he or she (or it) doesn't need to appear (the narrator can merely narrate from the captions).

- Story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end that follow or modify in some clear way a basic narrative arc.

- Story can be fiction or non-fiction, fantastic or realistic.

- Story should take place at four or more different moments in time. The second moment should occur at least one year after the first, the third at least ten years after the second, the fourth at least forty years before the first.

- These moments should not be narrated in chronological order and do not need to be presented in the T, T+1, T+10, T-40 order listed above. E.g., you can begin at T+10, shift to T-40, then T, then T+1, then back to T, and so on.

- Story should present at least two additional moments, one in the historical past, one in the (more or less far) future, that are not (necessarily) part of the main narrative.

- Two panels of the comic should be based on pictorial images in the Zimmerli Museum.

- Story can use multiple generations, time travel, historical investigation, or strories within stories (but none of these narrative devices is required).

Work solo, collaboratively, or in a small group (each member responsible for five pages of story). As an alternative: you can develop a plot collaboratively in class, then each make (and modify) your own version of the story. In any case, discuss the project as a group before pursuing whichever approach you select.

We'll work on this comic for the next two weeks. For next week: (1) visit the Zimmerli and take notes, make sketches, photograph, etc. at leat two images on which to base some panels; bring this work to class; and (2) prepare and turn in a 1-2 page plot outline.

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 8

Comics in Brunetti:

- Seth, from It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken (242)

- Chris Ware, from Jimmy Corrigan (352)

Timescale Comics Project

Begin working on the project. Visit the Zimmerli and take notes, make sketches, photograph, etc. of at leat two images on which to base some panels. Bring this prep material to the next class. Make a note of the artist, title of the work, and year of its making. We'll pass these around and discuss them.

Prepare a 1-2 page story outline. Bring two printed copies to class. We'll share and discuss these in class.

Week Eight

In class

Work Due

Interview comic panels and title splash. Scan your work (if hand drawn). 600-800 dpi recommended for black and white line art. 300 dpi for color. Save each panel as a separate TIFF file (with LZW compression).

Bring TWO (laser) printed copies of your work (one for me and one to pass around) and an electronic copy (e.g., on a flash drive) to class.

We'll put the full comic together in class using Comic Life or Adobe.

Of Interest

Jason Fraspin, assorted comics

More on Time and Narrative in Comics

- Crumb, "A Short History of America"

- McGuire, "Here": p. 89, p. 91, p. 93

- Hernandez, "Flies on the Ceiling": p. 201, p. 202, p. 203.

- Huizenga, "The Sunset" (p. 285)

Timescale Comics Project

Tell a comics story in five or more pages using words, pictures, graphic devices, page design, etc.

- Story should have a narrator, although he or she (or it) doesn't need to appear (the narrator can merely narrate from the captions).

- Story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end that follow or modify in some clear way a basic narrative arc.

- Story can be fiction or non-fiction, fantastic or realistic.

- Story should take place at four or more different moments in time. The second moment should occur at least one year after the first, the third at least ten years after the second, the fourth at least forty years before the first.

- These moments should not be narrated in chronological order and do not need to be presented in the T, T+1, T+10, T-40 order listed above. E.g., you can begin at T+10, shift to T-40, then T, then T+1, then back to T, and so on.

- Story should present at least two additional moments, one in the historical past, one in the (more or less far) future, that are not (necessarily) part of the main narrative.

- Two panels of the comic should be based on pictorial images in the Zimmerli Museum.

- Story can use multiple generations, time travel, historical investigation, or strories within stories (but none of these narrative devices is required).

Work solo, collaboratively, or in a small group (each member responsible for five pages of story). As an alternative: you can develop a plot collaboratively in class, then each make (and modify) your own version of the story. In any case, discuss the project as a group before pursuing whichever approach you select.

We'll work on this comic for the next two weeks. For next week: (1) visit the Zimmerli and take notes, make sketches, photograph, etc. at leat two images on which to base some panels; bring this work to class; and (2) prepare and turn in a 1-2 page plot outline.

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Joris Driest, "Subjective Narration in Comics"

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapters 7 & 8

Comics in Brunetti:

- Seth, from It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken (242)

- Chris Ware, from Jimmy Corrigan (352)

Linked Comics:

- Jason Fraspin, assorted comics

Timescale Comics Project

Begin working on the project. Visit the Zimmerli and take notes, make sketches, photograph, etc. of at leat two images on which to base some panels. Bring this prep material to the next class. Make a note of the artist, title of the work, and year of its making. We'll pass these around and discuss them.

UPDATE: The story outline/breakdwon will be due next week (Nov. 6).

Week Seven

In class

Weekly Presentation

Kyle and Fangxing present on Understanding Comics, chapter 6.

No Zombie Comic This Week

Instead, a four-panel political dream comic by Jesse Reklaw.

Technical Talk: File Types

Screen resolutions, print resolution, JPEGs, GIFs, TIFFs, PDFs, etc.

Narrative Arcs

We'll talk about some the readings for the last two weeks in order to test, illustrate, and elaborate the classic narrative arc pattern described in DW-WP.

Return to Page Design

- Comixpress, Technical Specs

- GX Comics Templates

- Zander Cannon, Tips and Tricks: Writing for Comics

- Jack Kirby, Captain America vs Batroc the Leaper (3 x 3 action sequence)

- Jack Kirby, Forever People (five panels in three tiers)

- Jack Kirby, Devil Dinosaur (three panels in two tiers)

- Jack Cole, Plastic Man (Plastic Man #7, Spring 1947). Cole balances a scene dominated by Dr Volt's thin blue outfit in the upper left against a second scene dominated by Woozy Wink's dotted, much fuller green outfit in lower right. Notice also how each of the two scenes has its own secondary or background activity: the cat and mouse drama above, the odd bespectacled figure (Plastic Man in disguise) below.

- Eduardo Risso, page 100 Bullets. A page from the Counterfifth Detective sequence of the series; seven panels in three tiers narrating an event we never see, a devastating punch, and its aftermath.

- John Porcellino, Armadillo Story

- Takehiko Inoue, Vagabond, chapter 12, page 8. A page of impersonal narration and aspect-to-aspect transitions; note the bleeds on one side but not the other and the different thicknesses between the horizontal and vertical gutters; reads right to left, in the Japanese style; four panels in three tiers; compare with the second Kirby example above.

Minute Movie PDF Redux

Maybe.

Interview Comic

Work on the interview comic project. The comic is (for the most part) described under Week 6. However, the chapter on Structuring Story in Abel and Madden adds clarity to the the narrative portion of the project. How can you compress the protagonist » spark » escalation » climax » denouement pattern into your relatively short work?

Here is another example of an interview comic by Chester Brown, who, as these examples suggest, appears to be quite a fan of this genre.

Mike Russell, Culture Pulp: Jeff Smith/Bone interview (I think).

(And while I'm at it, here is Mike Russell's brief history of super-heroes in film, an informational comic he made for the Oregonian in 2004.)

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Zander Cannon, Tips and Tricks: Writing for Comics

- Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, chap. 14 (Reproduction: scanning, etc.).

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 7

Comics in Brunetti: Since the next project start date has been moved to next week, re-read last week's related readings in Brunetti.

Optional: I've uploaded the complete Crepax graphic novel to Sakai. Take a look.

Interview Comic/Comic Interview

Finish drawing your panels. Design and draw your title splash. Scan your work (if hand drawn). 600-800 dpi recommended. Save each panel as a separate TIFF file (with LZW compression if you like).

Bring TWO (laser) printed copies of your work (one for me and one to pass around) and an electronic copy (e.g., on a flash drive) to class.

Again, you'll put the full comic together in class using Comic Life or Adobe.

If you cannot make it to next week's class, do not leave your partner(s) in a bad spot. Send them digital copies of your panels via email so that they can finish their version of the comic in class. They'll then send you copies of their panels and you'll need to finish your own version independently. (Upload to our ScribdD.com group as soon as you can).

Week Six

In class

Weekly Presentation

Returns next week. This week I want to use the time to catch up with some of the reading from the last two weeks.

Weekly Zombie Comic

Ed Piskor, Wordless Zombie Comic of the Week

Minute Movie Project

Lay out and collate your movie comic in Comic Life. Make it your comic has title page or large title panel with a credits. Save the final version as a PDF and upload to the 402_fall08 group on Scribd.com.

Page Layout

We'll look at some examples from the reading for last week and also at some of these mostly classic examples:

- E. C. Segar, Thimble Theater (1930)

- George Herriman, Krazy Kat (1922)

- George Herriman, Krazy Kat (1922)

- Chris Ware, Candide (book-cover design)

- Cowboy Henk (foreign, very)

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen (opening page)

- Steranko, Nick Fury page

- David B., Epileptic, page 163

- David B., Epileptic, page 164

- Nick Bertozzi and Harvey Pekar, "Greetings from Ohio"

And: An example of adventurous page structure from the diary comics.

Splash Page Examples

Here they are:

- Jack Kirby splash: Donnegan Daffy's Chair

- A different Jack Kirby splash: Hello from Jack

- Full page splash: Green Lantern

- Jack Kirby, Two-page OMAC splash (OMAC #2)

- Paul Pope, Kirby tribute (Solo #3)

Interview Comic Assignment

Working in groups of two or three, produce a reciprocal interview comic: i.e., one in which you interrogate each other on and discuss one or a small range of related topics.

Here is an example: Steve Murray and Chester Brown, "Brown Now".

As with this example, your comic must have some kind of plot, including at least one significant event. The event can come at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end (as in the Murray and Brown comic).

Also as with the Murray and Brown example, each participant will draw the panels in which he or she asks or answers a question.

Content-wise, then, this comic should do two things. First, it should present a reciprocal interview in which each participant learns something, in some detail, about the other participant. This can be biographical, philosophical, political, culinary, academic, sexual (with the appropriate care), aesthetic, athletic, martial, etc.

For instance, you might discuss drawing or comics, or something you both liked or disliked in your distant childhood.

However, be sure to AVOID: (1) the election; (2) this class; (3) films, since we just did that.

Second, the comic should tell a minimal story, including at least one significant event (as in panels 8 & 9 of the Murray-Brown strip). The event can come at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end. If it's at the beginning, your interview dialogue (or "trialogue") can develop in reaction to the event: "Did you see that?!" "Yeah!" "What did you think of it?" And so on.

Or the plot can take place in the background of your strip. You're there talking in the foreground, and some series of actions is taking place behind you or above or around you. Or, your discussion takes place in the background with the story taking place in the foreground. Something like Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

The story can even be serious (or comical) CONTRAST = e.g., a traditional superhero team-up in which, while doing all sorts of life-saving and derring-do, you conduct a mostly serious conversation about something else, unconnected (or only metaphorical or metonymically connected to what you images show). Thus something like this:

but with interview dialogue instead of Bob Hnaey's classic silver-age dialogue.

Requirements

Each participant is responsible for (1) at least six panels and (2) a splash panel of at least one third of a page containing an image, the comic's title, and credits. In other words, you'll have several versions of the first page, one for each participant. Agree in advance on whether this will be a one-third, half, two-thirds, or full page splash (no OMAC style two-page splashes).

An example of a splash: Jack Kirby Splash.

(For more, see the examples listed in the section above.)

For this comic, you'll need to scan your work (if not drawn on a computer) and bring scanned versions of your work to the next class.

Color is optional, but never frowned upon. You may letter by hand or digitally (e.g., in Comic Life).

Each participant may represent him or herself realistically or symbolically. It's your avatar. (You may even change from panel, although this can be risky if it distracts from the other content.) The only real rule is that how you depict yourself does not interfere with the legibility of the comic.

Process

The process in sum:

- Form your pairs or triples

- Interview = generate story and draft of script

- Collaboratively thumbnail the comic

- Draw your panels and title splashes

- Scan drawings; save panels as TIFF files

- Combine panels, layout, etc.; add extra lettering, captions, to maximize transitions, etc. in the next class

For advice on scanning drawings, see the PRINT section by Jordan Crane in A Guide to Reproduction (PDF).

Or find an online tutorial by searching for "scanning line art" in Google. Generally, if you're doing a straight line art scan, 600dpi-800dpi is good.

More Examples of Interview Comics

- Nick Bertozzi and Harvey Pekar, "Greetings from Ohio" (again, as interview example)

- Crumb and Pekar, Lunch with Carmella (Brunetti 322).

- Crumb and Pekar, Excerpt

- Jay Lynch and Ed Piskor, Chester Gould (not really an interview with Gould, creator of Dick Tracy; more a memoir of strange encounter with him)

Also take a look at the excerpt from Art Spiegelman's Maus (Brunetti 149), in which Spiegelman interviews his father, a holocaust survivor.

Homework

Updated: October 10

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, chap. 9 (Structuring the Story).

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 6

- Benoit Peeters, "Four Conceptions of the Page", trans. Jesse Cohn (ImageText 3.3).

Comics in Brunetti:

- McGuire, "Here" (88)

- Hernandez, "Flies on the Ceiling" (191)

- Huizenga, "The Sunset" (283)

- Crumb, "A Short History of America" (299)

Linked comics:

- Alan Moore and Rick Veitch, Greyshirt story: "How Things Work Out" (Tomorrow Stories #2, 1999). Note: you'll need to register with Issuu to read this one.

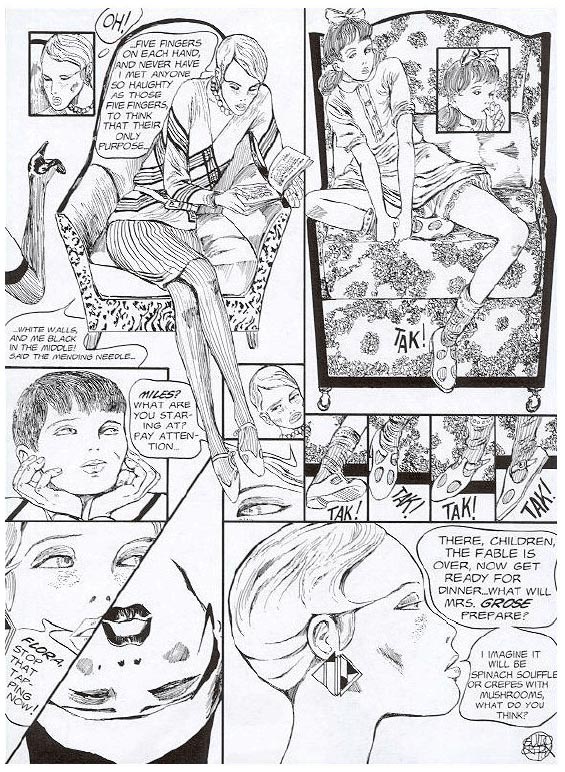

For more interesting page and panel design, see Shintaro Kago's Abstraction (the one we looked at in class), and this sample page from a modernized erotic adaptation of Henry James's The Turn of the Screw by the Italian comics artist Guido Crepax (1989):

While alluding to an underlying grid, Crepax uses symmetrical panels, insets, overlaps, diagonals, repetition, lush pieces of furniture that almost become a part of the characters sitting in them, and characters drawn in such a way that they might dream of such things as becoming lush pieces of furniture.

Interview Comic/Comic Interview

Update: We'll start this project officially in the next class, and the work listed below will be due, now, the following week. However, feel free to work on the project in advance. Any progress made now will mean less work ahead.

Draw your panels. Design and draw your title splash. Scan your work (if hand drawn). 600-800 dpi recommended. Save each panel as a separate TIFF file (with LZW compression if you like). Bring two (laser) printed copies of your work and an electronic copy (e.g., on a flash drive) to class.

Again, you'll put the full comic together in class.

If you cannot make it to next week's class, do not leave your partner(s) in a bad spot. Send them digital copies of your panels via email so that they can finish their version of the comic in class. They'll then send you copies of their panels and you'll need to finish your own version independently. (Upload to our ScribdD.com group as soon as you can).

Week Five

Note: Yes, there is class today.

In class

Weekly Presentation

Ashley and Tim, I believe, will present on chapter 5 of McCloud's book.

Diary Comics

Some things to look at.

Time Divisions: regular or variable, linear or non-linear.

Styles of narration:

- POV narration (showing us what you see)

- Third-person narration (showing us yourself)

- Symbolic narration (using metonymy, metaphor, synechdoche, etc. to show us icons standing for what you see, what happens, what you do, think, etc.)

- Inner/psychological narration (showing us primarily what you think or feel)

- Expressionistic narration (see my example)

Grading Criteria

We didn't get to talk about this much last time, so we'll look these over again today, with reference to your diary comics.

Below are the general grading criteria for the composing graphic narratives course. Specific assignments might have some additional criteria.

- Complexity: How much the work does, how much content and technique it, how many different pieces it brings together, given what it can. For instance, in the pictureless comic, all else being equal, a work varying the size of its panels would exhibit greater complexity than one that did not; and one that uses word balloons, sound effects, motion lines, and emanata would be more complex than one using only word balloons and sound effects. Paradoxically, making a comic very simple can be a sign of complexity, given that formal simplification is a possible technique.

- Creativity: The degree to which the work does clever, surprising, adventurous things with the requirements of the assignment and the resources of comics and narrative.

- Coherence: How well a narrative holds together as a complete whole.

- Clarity: The clarity of panel content and transition. How easy or difficult is it for your reader to tell what is going on in a panel or to effect closure between series of panels. Clarity is a relative value. Some narratives exploit ambiguity or obscurity. Clarity becomes a problem when ambiguous or obscure narration is not a (clear) intention of the work.

- Comprehensiveness: The degree to which your work satisfies the basic requirements of the assignment. (E.g., if the assignment specifies that your narrative take place in a cold climate, does it take place in one? If the assignment specifies no more than three characters in at least nine panels, do you have four characters? only six panels?)

- Care (or Correctness): Correct spelling, submitting all your pages, having all the basic pieces in place (e.g., title).

Minute Movie Project

Continue working on the project in your groups.

Again: The Arntz isotypes should be your main visual vocabulary. However, you may draw or otherwise make your own backgrounds. And where necessary, you may supplement the isotypes with non-conflicting images.

Page orientation can be landscape or portrait. You can use the printer default size of 8.5 x 11 inches or another printable size (but don't forget to allow for margins). You can also find a range of standard comic layout templates online (printers tend to offer these to help potential clients format their work; for example: GX Comics Templates).

Save an editable file or files of all your work. The final version (due at the start of nextclass) should be saved as PDF and uploaded to the ScribD group for this class. You can save your multiple files as single PDF in either Photoshop or Acrobat Professional. If we have time, however, we might collate complete projects using InDesign so that you can get introduction to that program as well.

Some resources:

- Literary Tropes

- Photoshop Guide/Tutorial

- Making Speech Bubbles, etc. in Photoshop

- Make Custom Shape from Isotype using this Photoshop tutorial

- Free Fonts from Blambot

- And again: Gerd Arntz Web Archive

Homework

Updated: Sunday, Oct. 5Only light reading for this week. I'm hoping we'll have a chance to catch up on discussing some of the other readings. We'll return to McCloud and the presentations next week.

The main homework, as I said in class, is for each of you to complete your section of the film re-telling (& criticism) comic. Bring your files to class. We'll spend the first part of the class laying out and combining your work in Comic Life.

We'll discuss page layout and paneling, with reference to Abel and Madden, in class. We'll also begin a new collaborative project in the second half of the class and preview an upcoming individual project.

For some ideas on using isotypes, take a look at Austin Kleon's post: Gerd Arntz and the Woodcut Origins of the Stick Figure. Scroll down to see several good examples of Arntz's work where he uses his figures, as you're doing, to tell stories and convey information.

Finally, if you haven't done so already, register at ScribD and join the class group. To do the latter, register and then search for 402_fall08. Once you've the group, apply to join. I'll check the new applications next week and add you to the group.

Week Four

In class

Weekly Presentation

Katie and Mike present an action-packed summary and analysis of Understanding Comics,chapter four. Meanwhile, Annalise and Brielle help us to make sense of Wolk's essay on space, time, and comics.

Comics of Interest

More comics journalism: Jeffrey Cane, Peter Hamlin, and Jacky Myint, The Bear Trap (Portfolio).

Fixed from last week: A kind of journal comic by Harvey Kurtzman: "I Went to a 'Perry Como' Rehearsal" (late 1950s).

Harvey Kurtzman, "Hey, Look!".

Wolk's example from Seth's Clyde Fans.

McCloud and Wolk

Some of Wolk's key terms and ideas:

- "cartooning as interpretation" (121)

- "cartoonist's line" as "signature" (123)

- "legibility" (124) – very important

- "two different kind of information" [on the page] (126)

- "change over time" (130) = "space in time" (125)

- "pregnant moment" (131)

Wolk also argues that for many comics: "The cartoonist's image-world is a metaphorical representation of our own" (134). He unfolds two possibilities from this idea:

- "experiencing space-through-time in a way that's different form our personal perspective" (134) = representation of another, distinctive subjectivity; and

- "the concept of a literal separate reality that is also, in consequential ways, default reality" (134) = fantasy worlds, surreal worlds, metaphysical worlds,dream, worlds, alternate realities, etc.

When we take away narrative focus or fullness, when we slow down the narrative, or increase the space between the moments of crisis, e.g., in the pictureless comics or the diary comics, we get just "another world, which is this world" (literally or metaphorically).

Minute Movie Project

Start working on the project in your groups. Return to planning, researching, and scripting/storyboarding/thumbnailing, both collaboratively and individually. Work on a consistent visual plan for the work.

Next, start making the actual comic. The Arntz isotypes should be your main visual vocabulary. However, you may draw or otherwise make your own backgrounds. And where necessary, you may supplement the isotypes with non-conflicting images.

Page orientation can be landscape or portrait. You can use the printer default size of 8.5 x 11 inches or another printable size (but don't forget to allow for margins). You can also find a range of standard comic layout templates online (printers tend to offer these to help potential clients format their work).

Save an editable file or files of all your work. The final version (due date will be discussed in class) should be saved as PDF and uploaded to the ScribD group for this class. You can save your multiple files as single PDF in either Photoshop or Acrobat Professional. If we have time, however, we might collate complete projects using InDesign so that you can get introduction to that program as well.

Some resources:

- Photoshop Guide/Tutorial

- Free Fonts from Blambot

- And again: Gerd Arntz Web Archive

- More . . .

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, a second look at chapter 6.

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 5.

Comics in Brunetti:

- No Brunetti reading this week.

Both of these pieces are narrated biographical comics. While not film stories, they can suggest ways for narrating your "retold" film comics.

Linked comics:

- Joel Priddy, "Onion Jack" (via Sakai).

- Kevin Huizenga, "Glenn Ganges" (online at USS Catastrophe; there's also be a version available through via Sakai).

- Zombie Comics as Cultural Critique (I think): Chester Brown, "To Live with Culture" (apparently refers to an ad campaign in Toronto).

Minute Movie Comic

Complete draft of your section of the comic. Include summary, crticism, and trivia. We'll work on revising this draft in the next class. The final version of the project will be due at the start of the following class (Oct. 9).

Week Three

In class

Weekly Presentation

Daniel and Patrick, in jumpsuits, present their helpful summary of chapter three of Understanding Comics.

Opening Examples for Discussion

Unauthorized Photoshop mods and remixes of Scott McCloud's Google Chrome comic (last week's novelty): "Google's Chrome Comic Gets Bastardized 70 Different Ways".

A nice collection of banners from the Little Nemo classic Sunday comic strip.

Follow the panel transitions in Cliff Sterrett's Polly and Her Pals (March 3, 1929).

A kind of journal comic by Harvey Kurtzman: "I Went to a 'Perry Como' Rehearsal" (late 1950s).

Comics by Gilles Ciment made with scanned stamps (French):

Ciment's comic is a compressed retelling of a Tintin graphic novel. Which brings us to the next topic of the day . . .

Adobe Creative Suit 3 and Making Comics

Last week we looked briefly at Comic Life and had a quick look at Photoshop. Today we'll go over (more slowly) some basic uses of Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, and Flash Professional in the production of graphic narratives.

Some image sources to which we'll return:

Comic Jumble Exercise

Working in groups of three on the Mac grands, complete the jumble comics exercise described on pages 46-47 of the Abel & Madden textbook.

Here are the original instructions.

For this exercise we'll use the beautiful Sunday Comics Sections from the Times-Picayune, June 25, 1939 (via the hard work and kindness of ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive).

Work in Photoshop and, if available, Comic Life.

When you've finished, save your comic jumble twice: (1) as an editable PDF, Tiff, or PSD and (2) as a compressed PDF. Upload the second (compressed) version to our "402_fall08" group on ScribD.

This exercise should serve as a first Photoshop warm-up.

Diary Comic Revision/Modification

Working in groups of three on the grand Macs, use Photoshop etc. to revise, modify, re-design and re-illustrate a page of each group member's diary.

First, read through each other's comics. Then select a part of each to re-make digitally. Discuss ways to do this. Then implement.

This exercise should serve as a second Photoshop warm-up.

Storyline Compression and Film Criticism Project

Also known as the "Minute Movie Comic" project.

Working in a group of four, you'll produce a digital comic in which you summarize, critically discuss, and provide some trivia related to a feature film.

Your primary method of illustration will be using Gerd Arntz's isotype pictograms, which we looked at previously.

Each group member will be responsible for 6-9 panels (total) on two to three pages.

Narration is required. Narration can be personal or impersonal; limited to caption boxes or spoken by a narrator. The narrator can be an avatar for the author(s) or a character from the film doing double work as a narrator (or multiple characters, each telling and commenting on a different part of the film).

You're translating the film narrative into a graphic narrative, necessarily compressing the story and adapting one visual system to another. Here think of the exercise we did last week, how a longer story was compressed into a shorter one.

In the process of your translation, you may also alter how the story is told. (But you shouldn't change the facts of the story.) For instance, you may decide to retell the story as a first-person narrative, or you may want to change the sequence of events. If the film moves forward in a linear fashion, you may want to start at the climax and retell the story as a flashback.

Not really examples but objects of comparison:

- Not So Great Summaries: Moulin Rouge

- Ryan Kelly, page of Ayn Rand biography

Begin your project today by choosing a film to work on, doing some basic research (for plot and trivia), deciding what you want to say, and then, together, working out your summary and critical remarks and dividing up the production work.

Next week you'll work on making your section of the comic in class.

Homework

Reading

Technical, critical, theoretical:

- Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, chapter 6.

- McCloud, Understanding Comics, chapter 4.

- Douglas Wolk, "Pictures, Words, and the Space between Them" (handout).

- Ron Rege Jr., Dave Choe, Brian Ralph, and Jordan Crane, A Guide to Reproduction (.pdf).

Comics in Brunetti:

- Robert Crumb, "Jelly Roll Morton's Voodoo Curse" (311)

- David Collier, "Ethel Catherwood Story" (337)

Both of these pieces are narrated biographical comics. While not film stories, they can suggest ways for narrating your "retold" film comics.

Linked comics:

- Joel Priddy, "Onion Jack" (moved to next week)

- Dash Shaw, "Cartooning Symbolia" (.pdf)

- Jordan Crane, Cloud Country (chap. 3)

Minute Movie Comic

Script and then storyboard/thumbnail your section of the comic. Bring extra copies of both to the next class for review and collection.

As noted, we'll work on making the actual comics in class.

Presentations

Prepare your presentations on McCloud, chap. 4, and Wolk, "Pictures, Words, and the Space between Them". Each team of presenters needs to prepare a one to two page outline/summary in which the main ideas of the reading are stated and key terms are defined (basically, your notes for your presentation). Upload your summaries to the ScribD group and bring a printed copy to class.

Here is an example of a written summary/outline. It's from another class, on games rather than comics, but covers similar material. It should help you with length and level of detail. Note that the attached summary is for two chapters. Each team of presenters for next week is responsible for only one chapter.

Week Two

In class

Scribd Sign-Up

Register for Scribd.

A sheet will be going around; please clearly add your email to the sheet. I'll use these to send you registration requests ("invitations") for Scribd and possibly also Sakai.

The Reading

Let's look at some examples from the reading for today. In particular, let's consider the form and function of the narrator or narrative voice in each of these.

More Examples

Google Chrome: The Comic by the Chrome Team and Scott McCloud.

Related: Patrick Montero, Interview with Scott McCloud, artist behind Google Chrome comic (Daily News).

Clip Art Comics

Source: Kennedy Rose, Anomaly

Activity: The Wrong Planet

Today's first group activity is Pahl Hluchan's "Wrong Planet" activity, described in the Abel & Madden textbook on page 31.

Activity: Power of Captions

Our second group activity is the exercise suggested by Austin Kleon's "The Power of Captions: Words Added to Pictures". Following Kleon's analysis and examples, you'll work in groups to create different gags, stories, or messages from the same image.

Among other things, we'll use this caption-writing activity for some preliminary practice with Photoshop and Comic Life.

Working in groups of 3-4, complete the following series of steps.

- Find/produce a mix of wordless images. There should be at least six of these. Half need to be drawn (by you or found online) or clip art; half should be photographs.

- Save the images to the local desktop and open them in Photoshop.

- Move one table over clockwise.

- Select 3-4 images from the selection open in Photoshop. Choose at least one drawing or piece of clip art and one photograph.

- For each image, come up with two VERY different captions or labels that (optimally) change how we would see these images in two very different, even opposing ways. Use Kleon�s blog article as a your paradigm.

- Duplicate the image as demonstrated by the instructor.

- Then use the Photoshop type tool (or Comic Life) to add your conflicting captions to each image-pair.

- Re-save the images, and upload them to one (or more) of your Scribd accounts. Then email he instructor links to these online versions.

Homework

Reading

Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, chap. 4, on transitions and closure. Optional: chap. 5, on drawing/penciling.

McCloud, Understanding Comics, chap. 3.

In preparation for this week's comics-making homework, read the following comics in Brunetti (pages in parentheses):

- James Kochalka, from Sketchbook Diaries (43-45)

- Lynda Barry, Ernie Pook's Comeek (46-47)

- John Porcellino, "The Bottle and Me" (269-70)

- Gabrielle Bell, "Cecil and Jordan in New York" (279-82)

- Some Harvey Pekar comics (322-28)

And some online comics:

- Tim Hamilton, Post-Traumatic (Smith Magazine)

- One or two more TBA

Comic Diary Assignment

Working by hand or using a graphics program, make ("keep") a diary comic for the next week. Images can be drawn or collaged.

Your comic should cover at least five different days, using at least 10 panels, on at least two pages.

If nothing much happens over the next few days, then try to capture that uneventfulness. You may use one panel per event or devote several panels to recording/narrating a particular event. If your roommate says something funny, then that might be a good thing to include. If you see an interesting object on the street, draw it or take its picture and include that in/as a panel.

You might want to develop a simple constraint to help structure the diary: e.g., record whatever happens each day at 1pm and 7pm, even if its the same thing three days in a row.

These can be humorous, meditative, exciting, calm, or action-packed. And the drawing/images can be as simple or complex, as cartoony or illustrative as want. Also, the style can vary with the content (something we'll work with more later in the semester).

In light of today's discussion: Pick and try to maintain a single narration technique throughout the (short) diary. For instance, will you use an avatar like Alison Bechdel or an external voice-over like Art Spiegelman? Will you be the focus of your diary, the main character of your daily story, or the detached reporter of the world you inhabit?

Try to use some of the basic comics conventions (motion lines, sound effects, thought balloons, expressive or irregular panel borders, etc.) that you began to experiment with in the pictureless comic.

Layout your own pages or select and print panel-layout templates from Comic Life (on all campus Macs).

Some comics for reference:

- Derik Badman, Hourly Comic (Febraury 1, 2007)

- The World Is Not Yellow

- James Kochalka, American Elf

- Kevin Huizenga, "Glenn Ganges: Time Traveling" (first page)

Your diary comic (printed or handmade) is due at the start of the next class (Sep. 18). If possible, also bring an electronic copy of the strip to class (e.g., via flash drive or email).

Iconic/Realistic Assignment

In chapter two of Understanding Comics, McCloud describes the continuum of icons, from the more realistic to the more purely iconic. For this homework exercise, select eight different comics from the Brunetti anthology. On a sheet of white paper, do your best to copy a character face/head from each of these and order them in a line from most iconic to most realistic. Under each face/head record the name of the cartoonist you're copying and the page you're copying from.

Don't worry about making perfect or even very close copies. Just do your best and make sure your label each with its source.

Note: As an alternative to lining up your copied heads, your can number them from 1 to 8, with one being the most realistic and 8 the most iconic.

Presentation

Over the next few weeks, you'll present short (five-minute or so) summaries of the critical and theoretical readings, beginning with Understanding Comics, chap. 3, for next week. Most of these will be in groups of two or three.

Summarize the theory or argument of the chapter, listing and defining any key words.

Find or create your own examples to illustrate the author's ideas (to supplement his or her own examples in the reading). Present these in Powerpoint or Keynote or via Acrobat or a graphics program (or if they're of your own creation, via Scribd).

The first presentation group will prepare and present a five-minute summary of McCloud's Understanding Comics, chap. 3.

Note: Those presenting first (i.e., next week) will not have to do the Iconic/Realistic assignment.

Week One

In class

Introduction

The Books: (1) Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, (2) Understanding Comics, (3) An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories.

Two conceptions of comics we'll be working with:

- Comics as information = approach comics in general as an evolving body of techniques for storing and communicating information, very often narrative information.

- Comics (or cartooning) as interpretation, an idea put forward by Douglas Wolk in his book Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean, parts of which we'll be reading shortly. Wolk argues that comics don't simply reflect or record or report on the world in straightforward way, but "interpret" (or subjectively distort) the world in particular ways – through the style of the cartoonist (how the world is shown) as much as through the representational content (what parts or versions of the world are shown).

After reviewing the syllabus, requirements, policies, etc., we'll examine some examples of comics.

Before and After Exercises

Description of exercise: In groups of four examine the linked examples. For each one, determine what happens before (what leads to) the image or depicted scene and what follows from it. In other words, construct a general story surrounding the image. Then, for each image, imagine a describe a panel preceding the image and another panel following it. What action is shown in the panel? What, if anything, is said?

For this activity, use these examples.

Comics Terminology

Review of some basic formal terminology used to talk about comics/graphic narrative.

Panel Lottery Activity

This is a variation of an activity designed by Abel and Madden, authors of Drawing Words.

For this activity, follow these instructions.

Homework

Reading

Abel & Madden, Drawing Words & Writing Pictures, preface, introduction, and chaps. 1 and 2. Read through the chapters but don't do the activities or homework assignments.

McCloud, Understanding Comics, skim chap. 1 for interest, read chap. 2 carefully.

Conrad Taylor, "But I Can't Draw!" (.pdf)

An assortment of short comics:

- Joe Sacco, excerpt from Soba (Brunetti 329-36)

- Chris Ware, "I Guess" (Brunetti 364-69)

- Alison Bechdel, "Compulsory Reading"

- Campbell Robertson, "Primary Pen & Ink: Raleigh, N.C.," May 5 2008 (NY Times)

- Art Spiegelman, "Eyeball" (New Yorker via Flickr)

Look at the Sacco excerpt with the Pictureless Comic assignment in mind. Notice how much work is being done by the non-figurative elements (panel shape, caption box angle and position, motion lines, emanata, music symbols, etc.).

In the Ware comic, somewhat by contrast, consider how the pictures, which do not fit cleanly or even logically with the words, nonetheless work to extend their meaning.

All five comics actively use narration, with a first-person narrator (or reporter) visually present, verbally self-referred to, or strongly implied. Consider the similarities and differences between them, and note the contrast with Mat Brinkman's wordless "Oaf" (Brunetti 73-76).

Bring the Brunetti anthology to the next class.

Pictureless Comic

Make a nine panel comic using any features of the form but NO pictures. That is: you can use word balloons, thought balloons, motion/speed lines, sound effects, fancy borders (including broken and overlapping borders), and emanata (see Drawing Words pages 7-8). You can even use impact symbols (i.e., the jagged shapes used to indicate the fact and intensity of impact in fight scenes, accidents, etc.). But you can't use any pictures (no figures, no backgrounds).

Your comic should contain the following elements, which it needs to convey non-pictorially:

- cold-climate setting

- two human and one non-human (animal or alien) characters

- one heavy object

Your comic should also include:

- a piece of dialogue (or captioned exposition) used as both a question and an answer (i.e., in different panels).

Note that, despite the absence of figures and scenery, your comic does not have to be set in the dark, or a snow storm, or a blinding light, or represent the subjective experience of a blind narrator. That is: you do not need to explain (internally) the absence of the usual pictorial content. Although you may do so if you wish.

You can make the comic using pen and paper or a graphics program. While you might want to vary panel size, layout, or borders as part of your comic, here is a 9-panel grid (.pdf) to help you get started.

Here is an example of a short pictureless comic by Abel and Madden.

Some more examples courtesy of Derik Badman:

- Lilli Carré's comic

- Siobhan Renfroe's comic

- No Images by Matt Madden (again)

- A Nancy comic by Ernie Bushmiller

Your pictureless comic (printed or handmade) is due at the start of the next class (Sep. 11). If possible, also bring an electronic copy of the strip to class (e.g., via flash drive or email). If this is a problem, however, the electronic version can wait.

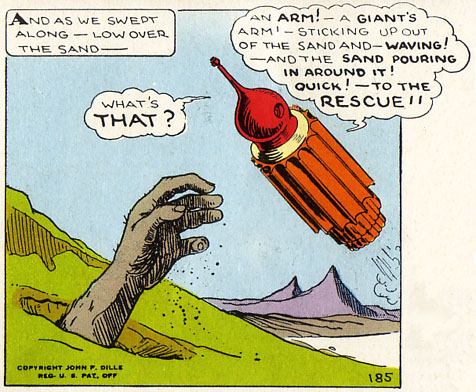

Skeezix Explained

Finally, here is the actual before and after for the baby Skeezix panel we discussed on Wednesday. It's from Frank King's long, long running Gasoline Alley newspaper strip, famous for its beautiful Sunday pages and its matching of narrative time to real time (i.e., for every year of its publication, the characters in the strip aged by one year – grew up, had kids, grew old, with the readers). Note the starry emanata.