BEFORE WE START…

On the section devoted to ‘The sources’, it has already been discussed that, more than probably, the text which we know today as ‘The Cheiroballistra is only the central surviving part of a once longer treatise. Actually, the fragment preserves no more than relatively accurate descriptions and dimensions of the components belonging to an artillery machine. In my opinion, our treatise at least is lacking a foreword with the original title and a final section with global assembly instructions.

Unfortunately for us, PH’s declaration of intentions -if it did exist- has gone missing with the foreword, so we are not told what kind of weapon the cheiroballistra was or what it was intended for. We are also devoid of the slightest hint on the way the components should be put together. Moreover, the instructions for making the components are far from being clear, in spite of the accompanying diagrams and the fortunate survival of equivalent components belonging to similar, but bigger, machines. In this context, I think that it is rather risky to state any beforehand conclusion on the little catapult’s finality or power output.

I believe that the most honest approach to the problem should be 'Let’s follow the surviving instructions to see what results from them’, instead of wantonly changing words and figures to make them fit into a pre-conceived idea, no matter how witty it may be.

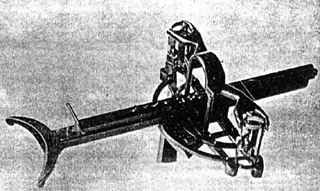

It will be no surprise if the successive attempts of reconstruction of the Cheiroballistra by different persons, from mid-nineteenth century to the present, either working ones or theoretical ones on paper, have ended in quite dissimilar outcomes. Machine designs from Alexandre Vincent and Victor Prou in the nineteenth century, Eric Marsden one century later, or the more or less present-day ones by Dietwulf Baatz, Alan Wilkins & Len Morgan, Michael Lewis, Digby Stevenson, Jeremy Barker, Bernard Jacobs, Ildar Kayumov or myself vary significantly. This is not the place to discuss them all and, on the following paragraphs I shall limit to explain briefly my own proposal. In case you are interested on delving more deeply into the subject, you can click HERE to receive my paper ‘Pseudo-Heron’s Cheiroballistra, a(nother) reconstruction. I.- Theoretics’ in Adobe .pdf format. It has been published in Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 11 , pp. 47-75.

1.Reconstruction by Prou

2.Reconstruction by Marsden

3.Reconstruction by Wilkins&Morgan

4.Reconstruction by Jacobs

SHOOTING THE CHEIROBALLISTRA

Click on any of these pictures for a larger view.

The first step in the loading process is to push the slider forwards, after disengaging it from its lock, until the claw jumps over the bowstring.