October 2007

Monthly Archive

Monthly Archive

Of 4,500-year-old music, that is. Maybe. At least you can get a sense of the sounds that musical instruments from Sumer were capable of making by watching this YouTube video.

I haven’t been able to discover the basis on which the music itself was composed, and I can’t claim to know anything about ethnomusicological investigations of ancient Sumerian music.

There’s also a brief clip of someone playing the Ur harp reconstruction while another narrates Gilgamesh, but the narration is in English, not Sumerian.

1 comments Christopher Heard | ancient Near East, music, archaeology

Last season, Heroes introduced Star Trek alumnus George Takei in the role of Kaito Nakamura, father of the time-traveling Hiro Nakamura. During this season’s premiere, however, they killed him off. Bummer. But two other Trek alumni have entered the season 2 cast: Dominic Keating, formerly Malcolm Reed on Enterprise, showed up as some sort of Irish bad guy associated with the criminal group that found an amnesiac Peter Petrelli, and classic Trek’s Uhura, Nichelle Nichols, appeared near the end of this week’s episode as D. L. Hawkins’s mother.

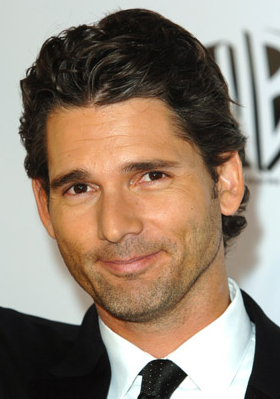

And, as you know, Heroes’s big bad from season 1, Zachary Quinto (Sylar), will be playing Spock next Christmas. Now the rumor is that Chris Pine—sounds almost like “Chris Pike,” doesn’t it?—is in negotiations to play Kirk. A couple of days ago, Eric Bana (Bruce Banner from The Hulk and Hector in Troy) was confirmed in the role of the lead villain, apparently named Nero, whose species has not yet been confirmed.

And, as you know, Heroes’s big bad from season 1, Zachary Quinto (Sylar), will be playing Spock next Christmas. Now the rumor is that Chris Pine—sounds almost like “Chris Pike,” doesn’t it?—is in negotiations to play Kirk. A couple of days ago, Eric Bana (Bruce Banner from The Hulk and Hector in Troy) was confirmed in the role of the lead villain, apparently named Nero, whose species has not yet been confirmed.

In other Trek news, scriptwriter Roberto Orci has confirmed that the film will focus (as it should!) on Kirk, Spock, and McCoy. We have confirmed casting for Spock, Uhura, Chekov, and a major villain; we know Kirk and McCoy will be in the movie, and casting possibliities for Scotty have been rumored as well. The film is scheduled to start filming in November and should premiere on Christmas Day 2008. What a great Christmas present!

A few days ago, I received—unsolicited—a copy of Bruce Waltke’s new Old Testament Theology (Amazon.com does not at this very moment list the book, despite the link to Amazon from the Zondervan web page). I had unexpectedly had a few minutes to spare last night, so I decided to dip into the volume. I read about the first eight pages or so of chapter 1, “The Basics of Old Testament Theology.” Based on those pages, I think I’m going to have a lot to disagree with in this book. For example, on p. 31, Waltke writes:

A few days ago, I received—unsolicited—a copy of Bruce Waltke’s new Old Testament Theology (Amazon.com does not at this very moment list the book, despite the link to Amazon from the Zondervan web page). I had unexpectedly had a few minutes to spare last night, so I decided to dip into the volume. I read about the first eight pages or so of chapter 1, “The Basics of Old Testament Theology.” Based on those pages, I think I’m going to have a lot to disagree with in this book. For example, on p. 31, Waltke writes:

Resting on the logic that one does not need to prove the “rightness” of presuppositions (for they would no longer constitute presuppositions) but only their “reasonableness” …

No, really. He writes that. “I don’t have to justify my presuppositions, because then they wouldn’t be presuppositions any more.” I should think that moving one’s presuppositions from presuppositions to justified claims should be a desideratum, but Waltke instead uses semantics as an escape hatch.

Or again, on p. 32:

… it is wrongheaded of the historicists to seek to penetrate to the historical event beyond the biblical text, for the events cannot be known apart from the texts that form the canon.

It’s just possible that Waltke is trying to get at a fairly subtle point in the paragraph that contains this quotation, but the quotation itself is maddening. “Don’t bother seeking the historical facts; just read the text” is obscurantist enough, but to make an epistemic claim that one cannot reconstruct historical events in ancient Israel or in Roman-era Palestine apart from the Bible is pretty much ridiculous. Maybe when Waltke writes the word “known” in this context he is talking in some quasi-mystical way about penetrating to the “real meaning” of the events, but the actual sentence makes it sound like you can’t know anything about Mesha’s conflict with the kings of Israel and Judah apart from 2 Kings; Mesha’s own (propogandistic) account, inscribed on the Mesha stele, is apparently deemed irrelevant. Or maybe he just means irrelevant to the theological task, though I’m not quite sure I’d agree even with that. Perhaps I’ll understand Waltke’s assertion better when I get to chapter 4, which the larger paragraph cross-references twice.

One more. On the matter of textual criticism and the difficulty of establishing the existence of—let alone identifying or reconstructing—a pristine “original” of any of our biblica texts, Waltke writes (p. 33, n. 15):

Roger Beckwith … plausibly speaks of multiple texts instead of an original text, but this point of view unnecessarily leaves exegetes and biblical theology without a firm foundation.

Did you catch that? The view that we shouldn’t speak about a single pristine Ur-text, but of multiple texts (go investigate the textual history of the book of Jeremiah if you need to see evidence in favor of this view), is “plausible,” but it’s inconvenient and doesn’t meet the felt need for a “firm foundation,” and—here’s the kicker—may therefore be discarded. Sorry, but “S has undesirable effect E” (or “S does not have desirable effect E,” as the speaker defines un/desirability) does not logically entail “S is false.”

3 comments Christopher Heard | biblical interpretation (methods), books, theology

The latest Bulletin of the Council of Societies for the Study of Religion arrived in my campus mailbox recently. One of the articles, “On the ‘Obvious’ in Science and Religion: Some Recent Flashpoints in the Media and the Academy,” by Benjamin Bennett-Carpenter. The article opens this way:

Call me crazy, but anytime I hear someone refer to something as “obvious,” a yellow flag goes up. Call it the perpetual critic in me or, perhaps, the intellectual. When anything “obvious” (and I will drop off with the quotation marks now that I have your attention to that word) is mentioned in regard to science or religion—or both together—then red flags fly.

Well, I’m sorry to set off Bennett-Carpenter’s yellow (or will they be red?) flags, but it’s obvious that somebody somewhere along the way failed to proofread the article very carefully, insofar as the article credits someone named “Peter Dawkins” with writing The God Delusion and The Selfish Gene. This error appears both in the main text and in the bibliography. Anybody know if Richard’s middle name is Peter?

The T&T Clark blog reports today that Lester Grabbe’s Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? (Continuum, 2007) is available “now” (which means, per the comment thread, “in a few days from now”) in paperback in the USA. Amazon.com has the book available for pre-order. It’s only $29.95—a steal for a Continuum title, though I may wait until the SBL meeting to see whether it might be discounted there at the Continuum booth (and while I finish some queued-up book reviews first).

The T&T Clark blog reports today that Lester Grabbe’s Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It? (Continuum, 2007) is available “now” (which means, per the comment thread, “in a few days from now”) in paperback in the USA. Amazon.com has the book available for pre-order. It’s only $29.95—a steal for a Continuum title, though I may wait until the SBL meeting to see whether it might be discounted there at the Continuum booth (and while I finish some queued-up book reviews first).

0 comments Christopher Heard | Israelite and Judean history, biblical interpretation (methods), books

The title of this post—you may notice that it is set in quotation marks, and in “title caps,” contrary to my usual practice—was the title of the 28th Annual William Green Lecture, presented tonight at Pepperdine by Dr. Rubel Shelly, longtime pulpit minister in Nashville and now on the faculty of Rochester College. I have to admit that I was skeptical of this particular combination of topic and speaker; I would characterize the result as “a mixed bag.”

Rubel introduced his talk with a few comments on the recent flurry of “anti-theist” publications, specifically mentioning recent books by Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion), Victor Stenger (God: The Failed Hypothesis), Daniel Dennett (Breaking the Spell), Christopher Hitchens (God is Not Great), and Sam Harris (Letter to a Christian Nation). I was deeply disappointed, though, when Rubel frankly showed no evidence whatsoever of having read any of these books. Whether Rubel has read any of them, I don’t know; what I do know is that he didn’t cite a single passage from any of them. Instead, to show that (some) atheists are “angry,” he cited book reviews of some of the volumes just listed, reviews published in the Wall Street Journal, Publisher’s Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, and so on. My a priori skepticism about a preacher speaking on “Why Are Atheists So Angry?” at a Christian university (and I say all this as a Christian who happens to deeply appreciate many aspects of Rubel Shelly’s preaching over the years) was now joined by a growing apprehension that we were about to be treated to a critique based not on readings of the criticized texts, but based only on book reviews. (In the interests of full disclosure: I have read the Dawkins, Hitchens, and Harris books listed above, but not those by Stenger or Dennett—no offense meant toward Stenger or Dennett, but I just haven’t had the time to get around to their books.)

Fortunately, that turned out not to be the case. Instead of a critique of any or all of the books listed above, Rubel offered three reasons why, in his judgment, contemporary atheists are “so angry.” Here they are, in the order he gave them. I will quote the reasons as they appeared on his PowerPoint slideshow, which did not always exactly reproduce the words he spoke verbally (but close enough, unless noted otherwise below).

1. “Many [atheists] are principled persons who take offense at what is done in God’s name.” Rubel specifically mentioned the violence of the Crusades and the Spanish Inquisition, attempts to gain power in the US through party politics, racism, sexism, televangelists fleecing their electronic flocks, sexual abuse of children by clergy, and Robertson/Falwell-type Schadenfreude. Rubel opined that “If there is any value in religion, religious reflection should generate humility and genuine respect for all creatures” (the best paraphrase I can give based on my hastily-scribbled notes). I was glad that Rubel led with this, as I think it is terribly important to acknowledge that many of the contemporary criticisms of religion—I am thinking of those that hinge on the behavior of believers—are quite well deserved. I substantially agreed with what Rubel said on this point, though I think his presentation had two notable weaknesses. First, Rubel did not address the criticism put forward that religion almost inherently leads to horrors, as would have been demanded by a real engagement with Hitchens or Dawkins (at least). Second, Rubel did not address the fact that God is depicted in the Christian Bible as endorsing, even demanding, actions that “principled persons” would normally consider reprehensible (the genocidal vision of the book of Joshua, for example). I’m not saying that I could do better—but I do think that it is incumbent on those of us, like Rubel and myself, who think that Christianity does offer an attractive vision of a better world (and I mean a better this-world, made so by people acting Christianly) to at least try to explain how we can think so in light of some truly terrifying Bible passages.

2. “[Atheists] are losing the intellectual battle over the issue of theism.” After giving a poor one-sentence description of the Big Bang, Rubel launched into a design argument using an analogy of Scrabble tiles on a student’s desk. Rubel actually used the phrases “argument from design” and “teleological argument,” even deploying Paley himself, and combined these with a brief fine-tuning argument. Rubel also cited Anthony Flew’s “conversion” (so to speak; Rubel was careful to state that Flew moved, at most, to a kind of Jeffersonian deism) and Francis Collins’s faith as evidence that “anti-theists are on the defensive” and therefore exhibit an “anger born of insecurity.” I couldn’t help but consider Rubel’s claim that atheists “are losing the intellectual battle” to be so much wishful thinking. Rubel’s attempts to strike a blow in that battle through a weak design argument certainly didn’t establish his point. The shortcomings of design arguments and fine-tuning arguments are pretty well known to those who really follow the “science and faith” debates. However, Rubel may have inadvertantly identified one possible source of atheist anger: anger at hearing the same weak theistic arguments over and over again as if rejoinders to those had never been offered from the atheist side.

3. “Every human being has a set of personal experiences to navigate.” If it’s not entirely clear what that has to do with atheist anger, well, bear with me a second. Rubel started this point with a longish anecdote about an acquaintance of his who had been severely injured in a military training accident. This person, who evidently had been raised in a Christian environment, found that his religious faith gave him strength to keep going. Rubel contrasted this with, um, Elton John (no, really), who has expressed anger at (some) Christians’ treatment of gays. “When a person is pain,” Rubel said, “God is a convenient foil for human anger.” I think this statement misses the boat entirely. Atheists are not angry at God; it would make no more sense for an atheist to be angry at the Judeo-Christian God than for me to be angry with Zeus. Atheists may very well grow angry at religious folk who go on and on about God’s beneficence in the face of widespread suffering in our world, and they may even take such suffering as evidence that God does not exist (I don’t think that conclusion follows, but I’ll save that for another time)—but they don’t get mad at a God that they don’t think exists.

Overall, I thought that Rubel’s first point was very good, his second claim was wishful thinking, and his third point missed the point. However, I can endorse, almost without reservation, Rubel’s final three bits of advice (at least as I have paraphrased them here) for his overwhelmingly Christian audience:

1. Don’t repeat the sins (his PowerPoint slide said “blunders,” but verbally he used the word “sins”) of the past (specifically, abuses of power in the name of religion).

2. Engage the serious intellectual dialogue (which—this is my point, not Rubel’s—cannot simply consist in trotting out the same old arguments over and over again as if they’d never been answered, and this applies to both sides).

3. Show Christlike love and compassion for hurting people.

You’ve heard of the “greening” of evangelical Christianity, that is, its awakening to ecological responsibility. You’ve heard of the “graying” of America, that is, a marked increase in the population of senior citizens relative to the entire population. I’d like to propose another color verb: “Browning.” The capital letter is important. With a lower-case b, “browning” is a culinary operation, usually performed on bread and such. “Browning,” with a capital B, I hereby define as “taking a subject about which one knows precious little, infusing it with crackpot conspiracy theories and a little gunfire, and selling the whole thing as historical fiction.” I suppose you can guess which Mr. Brown contributed his name to my neologism.

In January 2007 (the paperback edition is due in November 2007), Ballantine Books published The Alexandria Link, a novel by Steve Berry that attemps to concoct a Da Vinci Code style plot around Genesis 13:14–17. Reviewers were not particularly kind to the book, but I picked up the audiobook version from Audible nonetheless, looking for “ear candy” on my 40-minute commute. Thus far—about halfway through—I have indeed found the plot somewhat entertaining in a mindless sort of way. When my brain kicks in, however, all satisfaction with the book goes out the window.

In January 2007 (the paperback edition is due in November 2007), Ballantine Books published The Alexandria Link, a novel by Steve Berry that attemps to concoct a Da Vinci Code style plot around Genesis 13:14–17. Reviewers were not particularly kind to the book, but I picked up the audiobook version from Audible nonetheless, looking for “ear candy” on my 40-minute commute. Thus far—about halfway through—I have indeed found the plot somewhat entertaining in a mindless sort of way. When my brain kicks in, however, all satisfaction with the book goes out the window.

Much as Dan Brown made a real mess out of the New Testament and Christian history in The Da Vinci Code, Steve Berry makes a real mess out of the actual history of the transmission of the Hebrew Bible. The novel involves a race to find the contents of the lost library of Alexandria, texts and scrolls that were spirited away from the library by a mysterious secret society before the library was destroyed. According to one character early in the story, the library is supposed to contain a copy of the Septuagint, the old Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (originally, this term applied only to the translation of the Torah or Pentateuch, but the character doesn’t seem to be aware of the relevant distinction). According to this character—the Attorney General of the United States—all “Old Hebrew” copies of the Old Testament (yes, the characters are resolutely ignorant of the terms “Hebrew Bible” or “Tanakh” or even “Jewish Bible”) were lost before the Christian era, and thus the Old Testament is known to moderns only by means of the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate. By now, any reader educated in the actual textual history of the Tanakh knows that the characters’ knowledge is woefully deficient. But maybe we can forgive the Attorney General; he, after all, is no biblical scholar.

Unfortunately, the biblical scholar among the book’s characters isn’t that much better informed than the Attorney General. The title’s “Alexandria Link” is a person, Palestinian biblical scholar George Hadad (raised Muslim, and later a convert to Christianity, but now largely a non-believer), who happens to possess critical information about how to find the location where the Guardians preserve the lost library. At the end of chapter 20, readers are “treated” to a long, pedantic conversation between George Hadad and the story’s hero, ex-spy Cotton Malone. Malone’s ex-wife Pam is also present for this conversation, which I will go through in some detail. (Since I am listening to the audiobook version, what follows will be my own transcription from audio.)

“Christians tend to focus on the New Testament,” Hadad said. “Jews use the Old. …

Really. A Palestinian biblical scholar from the West Bank ought to know better than to call the scriptures used by Jews “the Old Testament.” “Old Testament” is entirely a Christian term. No Jew would use it to describe his or her scriptures, except as an accommodation to a recalcitrant Christian audience or interlocutor.

Hadad continues:

“I daresay most Christians have little understanding of the Old Testament, beyond thinking that the New is a fulfillment of the Old’s prophecies.”

Sad, but true.

Okay, this part of Hadad’s speech is more or less accurate, but the observations are fairly banal. They certainly are not earth-shattering for any but the most rigid a priori fundamentalists or the most ignorant of Bible readers. And these observations certainly wouldn’t come as news to the Bible’s editors and compilers. The lines about the flood are curiously put. The “seven pairs of clean/one pair of unclean” instructions and the “one pair of each kind” instruction appear side-by-side in the Bible; Hadad seems to make it sound like the two sets of instructions are widely scattered. By the way, all of these contradictions are easily explained by reference to source hypothesis, whether the classic Wellhausen formulation or some other version.

In the next line, Hadad trips up, and makes a statement that is truly stupid, at least for a biblical scholar—and also for the author of The Alexandria Link to have put in the mouth of any of his characters. Let’s rewind to the beginning of the sentence:

“Not to mention the dozens of doublets and triplets contained within the narratives, like the differing names used to describe God. One portion cites ‘YHWH,’ ‘Yahweh’; another, ‘Elohim.’ Wouldn’t you think at least God’s name could be consistent?”

Well, no. I mean, The Alexandria Link was presumably written by a single person, Steve Berry, who uses the names, titles, and epithets “George,” “Hadad,” “the Alexandria Link,” “the Palestinian,” “the older man,” and so on to refer to the character making the statements quoted above. No, there is absolutely no reason to think that the Bible would use only one term to refer to Israel’s God. If George Hadad had really been raised as a Muslim, he should surely know the many names and titles of God used in that faith, and if were really a biblical scholar, he should know that a varied vocabulary for divinities would be normal in the ancient Near East. Why, his own namesake, the Canaanite god Hadad, could also be known as “Ba’al,” “the Cloud-Rider,” “El’s son,” and so on. The big surprise would be if there were only one term used to refer to God in the Bible.

After a sentence hawking the author’s prior Cotton Malone novel, Hadad continues:

“Most now agree,” Hadad said, “that the Old Testament was composed by a host of writers over an extremely long period of time. A skillful combination of varied sources by scribal compilers. This conclusion is absolutely clear, and not new. A twelfth-century Spanish philosopher was one of the first to note that Genesis 12:6, ‘At that time the Canaanites were in the land,’ could not have been written by Moses. And how could Moses be the author of the Five Books, when the last book describes in detail the precise time and circumstances of his death? And the many literary asides, like when ancient place names are used, then the text notes that those places are still visible ‘to this day.’ This absolutely points to later influences shaping, expanding, and embellishing the text.”

Again, this is more or less accurate, but banal. The phrase “Most now agree” implies that the composite nature of the Tanakh was recognized only recently, but the rabbinic tractate Baba Bathra already stated that “the [Bible] was composed by a host of writers over an extremely long period of time” (not in those exact words, of course). And right after that, Hadad admits that these observations are “not new.”

Feeling a need to get in on the conversation, spy-turned-bookseller Malone chimes in:

Malone said, “And each time one of these redactions occurred, more of the original meaning was lost.”

Although Hadad answers “No doubt,” the conclusion actually does not follow from the evidence. In fact, Hadad’s own observations of the phenomena belie Malone’s conclusion. The transmission of traditions lying back of the Bible, and the various redactional processes that do indeed seem necessary to have produced the canonical forms of the biblical books, tended to add meaning, so to speak, rather than subtract it—and it’s those very doublets and triplets of which Hadad spoke earlier, those very contradictions, that demonstrate this. If the redactional process had eliminated a lot of “meaning,” then one would expect that some of that “meaning loss” would include the smoothing out of contradictions. But that is demonstrably not what happened, and Hadad’s own evidence belies Malone’s conclusion, which Hadad endorses.

Hadad ties up this part of his speech with the following conclusion:

“The best estimate is that the Old Testament was composed between 1,000 and 586 BCE. Later compositions came around 500 to 400 BCE. Then the text may have been tinkered with as late as 300 BCE. Nobody knows for sure. All we know is that the Old Testament is a patchwork, each segment written under different historical and political circumstances, expressing differing religious views.”

How much of the Tanakh originated between 1,000–586 BCE, as opposed to the later Persian and Hellenistic eras, is a matter of considerable debate. But note the incoherence of Hadad’s timeline: the Old Testament was composed between 1,000–586 BCE, and this was followed by “later compositions.” What are these “later compositions”? Hadad doesn’t say; I’d think of Chronicles, Ruth, Esther, Trito-Isaiah, and Ezra-Nehemiah, for example, but these are part of the Old Testament. Hadad’s terminology is just confused. And his assertion that the text may have been “tinkered with as late as 300 BCE” is really a bit silly, in light of the fact that the book of Daniel certainly was not written, much less added to the biblical canon, before about 165 BCE, and the divergences between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic Text show that small (but not necessarily insignificant) changes to the text continued to be made (accidentally or intentionally) into the Common Era.

After a short interruption from Cotton Malone, Hadad goes on:

“But what if the words have been altered to the point that the original message is no longer there? What if the Old Testament as we know is not, and never was, the Old Testament from its original time? Now that could change many things. … The Old Testament is fundamentally different from the New. Christians take the text of the New literally, even to the point of it being history. But the stories of the patriarchs, exodus, and the conquest of Canaan are not history. They are a creative expression of religious reform that happened in a place called Judah long ago. Granted, there are kernels of truth to the accounts, but they’re far more story than fact. Cain and Abel is a good example. At the time of that tale there were only four people on earth: Adam, Eve, Cain, and Abel. Yet Genesis 4:17 says, ‘Cain lay with his wife and she became pregnant.’ Where did the wife come from? Was it Eve? His mother? Wouldn’t that be eye-opening? Then, in recounting Adam’s bloodline, Genesis 5 says that Mehaelel lived 895 years, Jared 800 years, and Enoch 365 years. And Abraham? He was supposedly a hundred years old when Sarah gave birth to Isaac, and she was ninety.”

You’ll notice that, around the ellipses (which snip out a brief exchange about whether Cotton is a good listener), Hadad’s train of thought shifts to a completely different track. He starts out asking about the degree to which the text has changed from “the original message,” and then he goes off on some incongruities in scripture that resist taking the primeval narratives as accurate historiography—which almost no scholars do anyway, but which in any event has nothing to do with the accuracy of textual transmission. Then Hadad shifts back to the transmission issue, and in so doing, exposes his—and presumably the author’s—ignorance:

“The Old Testament as we currently know it is a result of translations. The Hebrew language of the original text passed out of usage around 500 BCE. So in order to understand the Old Testament, we must either accept the traditional Jewish interpretations, or seek guidance from modern dialects that are descendants of that lost Hebrew language. We can’t use the former method because the Jewish scholars who originally interpreted the text between 500 and 900 CE—a thousand or more years after they were first written—didn’t even know Old Hebrew, so they based their reconstructions on guesswork. The Old Testament, which many revere as the word of God, is nothing more than a haphazard translation.”

In the novel, Hadad is portrayed as one of the world’s foremost authorities on the Bible, world-renowned for his novel ideas (even though he’s supposed to be in hiding after an Israeli attempt on his life). Yet he garbles basic facts. The Hebrew language did not pass out of use around 500 BCE. It’s true, of course, that the Hebrew language changed over time, from Biblical Hebrew through Late Biblical Hebrew through Rabbinic Hebrew and so on, but it didn’t pass out of use. It may have passed out of use as the daily, default spoken language for Diaspora Jews—hence the need for the Targums or the Septuagint. And the other implication—that the Hebrew texts of the Tanakh disappeared around 500 BCE—is just silly; the canonical process was barely starting around 500 BCE, and significant portions of the Tanakh hadn’t even been written yet. Somehow, Jerome—he of Vulgate fame, who figures elsewhere in the book—was able to learn Hebrew and translate the Vulgate from Hebrew texts. Hadad knows this, and thus we can be sure that the author does too—and yet Berry has Hadad spin this fairy tale about the disappearance of the Hebrew language and Hebrew texts before many of those texts were even written.

“George, you and I have discussed this before. Scholars have debated the point for centuries. It’s nothing new.

Hadad threw him a sly smile. “But I haven’t finished explaining.”

And I haven’t finished fisking.

Admittedly, this may seem like a real waste of time, arguing with a fictional scholar. The danger, though, is that ignorant folk may pick up The Alexandria Link and—as happened with The Da Vinci Code—think that the characters actually know what they’re talking about.

John pushed one of my hot buttons by misusing the verb “deconstruct.” John was writing about “the tendency of evangelical translations of the Bible to ‘improve’ on the text in translation,” which can involve “the harmonization of scripture with subsequent traditions and expectations.” John has some good things to say in the entire post, but then he ends with this paragraph:

The goal of translation and interpretation cannot be to deconstruct textual content and eliminate the parts that reflect human limitations and keep the parts that express the power of God. The latter form an indissoluble whole with the former. The power of God is made perfect in the former. Eliminate scripture’s humanity, and you rob it of its divinity.

It’s hard to tell exactly what John means by “deconstruct” in this paragraph, but it has to be something like “take apart.” But that’s not what “deconstruct” means. As per the New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd ed., “to deconstruct” means to

analyze (a text or a linguistic or conceptual system) by deconstruction, typically in order to expose its hidden internal assumptions and contradictions and subvert its apparent significance or unity.

Clearly, that’s not what evangelical translators are doing when they smooth out the ruffles and harmonize texts (for example, in the [T]NIV rendering of Genesis 2:18–19. Quite the opposite, in fact. I imagine that someone will object that in English, unlike French, the semantic ranges of words are fixed by usage, not by committee. That’s fine and I understand that, but someone has to take a stand for the technical meanings of technical terms, and I guess in this case that someone will have to be me. So here is my plea to all readers of this blog: please, please, for the love of all that’s Derridean, please stop using “deconstruct” as a synonym for “disassemble.” Thank you very much in advance.

3 comments Christopher Heard | biblical interpretation (methods), Bible translation

Pauline Viviano has begun a series of posts on “violence in the Old Testament” on the America magazine blog. In part 1, Pauline introduces the problem and repudiates the interpretive move of “spiritualizing” the violence, making it all a metaphor for “spiritual warfare” (a concept she had to google because she never learned about it in Catholic school—lucky Pauline). In part 2, Pauline rejects the “two testaments, two gods” solution to the problem of divinely-perpetrated and divinely-sanctioned violence in the Old Testament.

That’s as far as the series has gotten to date. In the first paragraph of part 2, Pauline writes, “because of the complexity of the issue it will be necessary to stretch out my answer in a series of posts.” I should say so. This will be an interesting series to watch.

1 comments Christopher Heard | social issues, biblical interpretation (methods)